Makkin Mak Muwekma Wolwoolum, 'Akkoy Mak-Warep, Manne Mak Hiswi!

We are Muwekma Ohlone, Welcome To Our Land, Where We Are Born!

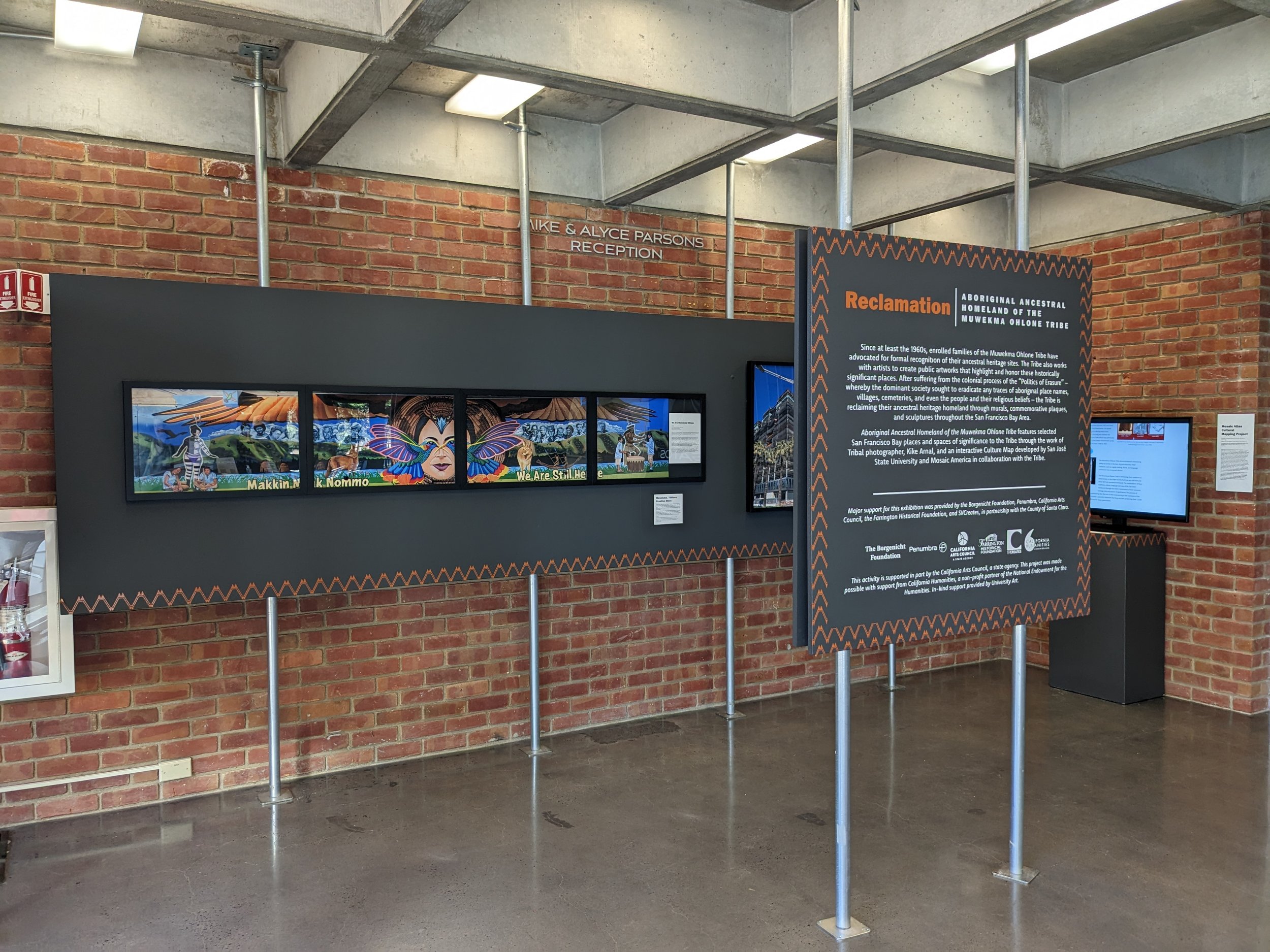

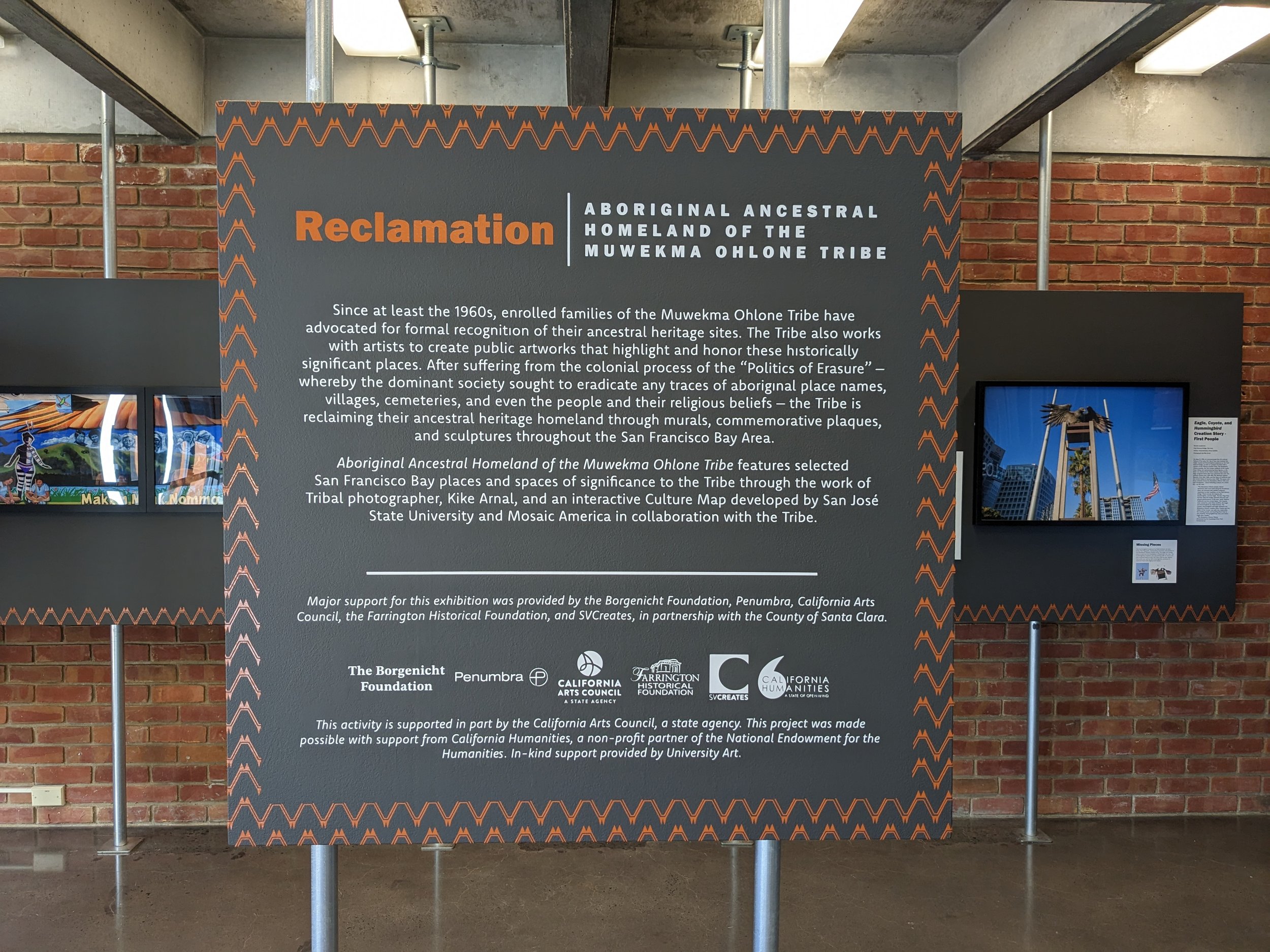

Reclamation: Aboriginal Ancestral Homeland of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe

Since at least the 1960s, enrolled families of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe have advocated for formal recognition of their ancestral heritage sites. The Tribe also works with artists to create public artworks that highlight and honor these historically significant places. After suffering from the colonial process of the “Politics of Erasure” – whereby the dominant society sought to eradicate any traces of aboriginal place names, villages, cemeteries, and even the people and their religious beliefs – the Tribe is reclaiming their ancestral heritage homeland through murals, commemorative plaques, and sculptures throughout the San Francisco Bay Area.

Aboriginal Ancestral Homeland of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe features selected San Francisco Bay places and spaces of significance to the Tribe through the work of Tribal photographer, Kike Arnal, and an interactive Culture Map developed by San José State University and Mosaic America in collaboration with the Tribe.

Major support for this exhibition was provided by the Borgenicht Foundation, Penumbra, the Farrington Historical Foundation, SVCreates, and in partnership with the County of Santa Clara.

This activity is supported in part by the California Arts Council, a state agency. Learn more at www.arts.ca.gov.

This project was made possible with support from California Humanities, a non-profit partner of the National Endowment for the Humanities. Visit www.calhum.org.

In-kind support provided by University Art.

We Are Muwekma Ohlone

We Are Muwekma Ohlone

Mural

San Fernando Street, San Jose

Artist: Alfonso Salazar

Photograph by Kike Arnal

This is a recent mural along the Thámien Rúmmey (Guadalupe River) San Fernando Street, San Jose. Art dedicated to the tribe and contemporary works, such as the mural titled “We are Muwekma, and We are Still Here” in San Jose, California by artist Alfonso Salazar was put there because of the river it represents the river of life because of the seasonal rhythms of life. Water is life. The mural is a prime example of the reclamation of place in the Bay Area.

The ancestors of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe are shown to be watching over the current members of the tribe and offering them guidance. These depictions in contemporary works remind them of their ancestors’ resilience and strength, sticking together during times of separation and attempts of erasure. Their ancestors have played an important role in educating the current generation and teaching them the ways of the past to continue on the traditions today. It is an important reminder to continuously respect the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone people that we occupy today. The mural calls back the origin story of the eagle, coyote, and hummingbird. It is used as a visual storytelling device to show how the oral history of the Muwekma sustains and connects members to one another. The mural also features the origin story of the Eagle, Coyote, and Hummingbird. Salazar says that the use of the creation story as a framing device for the mural was planned from the start in collaboration with Muwekma Ohlone leadership.

In the center is Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh with an eagle headpiece and hummingbird warrior face mask portrait. In the clouds above the mural are portraits of members that have made an impact in Muwekma Ohlone history. Each person in this section is from different walks of life, working in army service or government. Alfonso Salazar's statement for the mural is that the use of the creation story as a framing device and was planned from the start, and further planned out after communicating with the Muwekma Ohlone. The line and now title of the mural, “We Are Still Here” was suggested by Chairwoman Charlene Nijmeh, who also consented to being featured so prominently in the mural.

Eagle, Coyote, and Hummingbird | Creation Story - First People

Eagle, Coyote, and Hummingbird

Creation Story - First People

Bronze sculptures

Park Avenue Bridge, San Jose

Artists: Todd Andrews, Peter Schifrin

Photograph by Kike Arnal

On May 13, 1994, to commemorate the rich cultural history of the area, the City of San Jose unveiled the Eagle, Coyote and Hummingbird sculptures on the Park Avenue bridge, as well as a plaque inscribed with a version of the Ohlone creation story.

The Muwekma Ohlone people, the first known residents of the Santa Clara Valley, are represented by these figures, as the three are central to the Tribe’s creation story. Nearby flags recognize those who have governed San Jose: the Spanish Empire from 1769-1821; the Mexican Federal Republic from 1822-1846; and the State of California and the United States of America since 1850. This space and these artworks honor the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and later immigrants – those following a dream of a better life – to San Jose.

“The Muwekma Ohlone people, Native Americans who once lived along the Guadalupe River, are honored with animal sculptures important to their tradition, on the Park Avenue Bridge. These include the Coyote, the Hummingbird, and the Eagle. The four flags that fly from atop the bridge represent the past and present governments of the area: Spain, Mexico, California and the United States. The Coyotes were created by artist Peter Schiffrin; the Eagle and Hummingbirds by Todd Andrews.

The Coyote, Hummingbird and Eagle represent the Muwekma Ohlone creation story. Coyote was the father of the human race who was responsible for creating people and teaching them how to live properly. Hummingbird was wise and clever. Eagle was a leader.”

The Missing Pieces

Two Hummingbird sculptures by Todd Andrews sat atop thirty-foot flag poles, representing cleverness and wisdom in the Muwekma Ohlone creation story.

The eagles still reside atop their flag poles at this Park Street installation in Downtown San Jose. The Hummingbirds are now missing. The Tribe must be ever vigilant that public art, such as the hummingbirds and the plaque at Tamien Station, continues to represent them with dignity and respect.

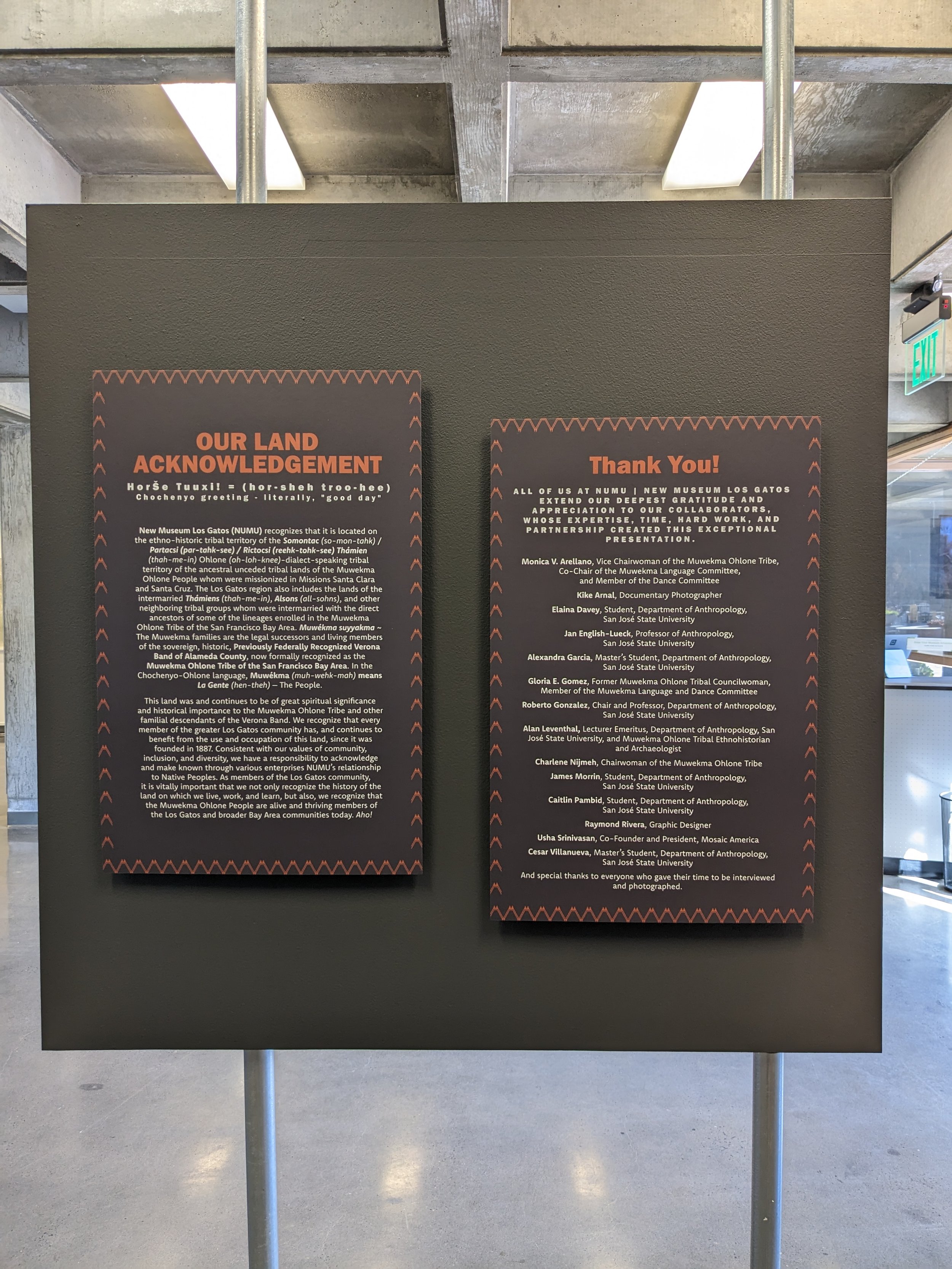

Máyyan Šáatošikma (Coyote Hills)

Máyyan Šáatošikma (Coyote Hills)

Mánni Muwékma Kúksú Hóowok Yatiš Túnnešte-tka

(Place Where the People of the Kúksú [Bighead] Pendants are Buried) Coyote Hills

East Bay Regional Park District, Fremont

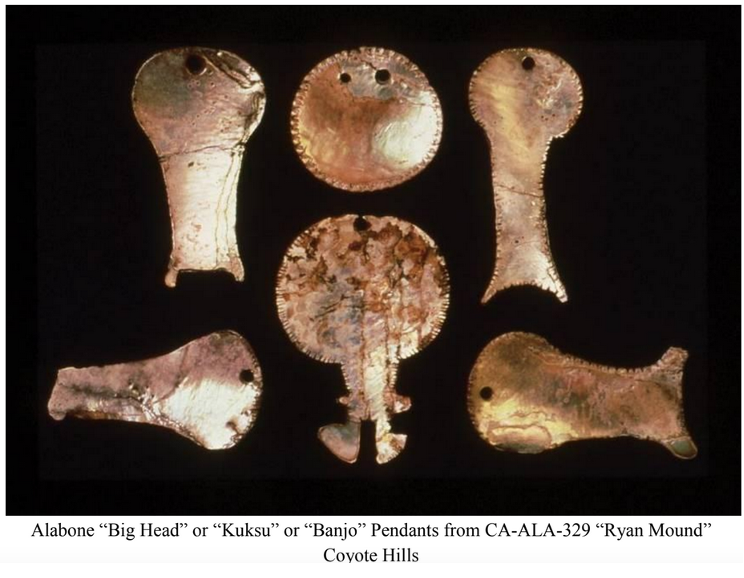

Máyyan Šáatošikma, the Muwekma Ohlone name for the Coyote Hills located near the East Bay Town of Newark, is the location of at least four major ancestral Muwekma mortuary earthen “shell” mounds.

Two of these had been mostly destroyed, however, two of the larger ones which were excavated by several university archaeological field schools in the 1950s and 1960s, have been analyzed and published. One of these mounds, CA-ALA-329, was excavated by Stanford and San Jose State Universities, has yielded approximately 500 ancestral remains dating from 100 BCE to 1767 CE, just before Spanish expansion into Alta California.

The analysis of the assemblages from this site was completed in 1993 by Muwekma Tribal archaeologist Alan Leventhal. This site yielded the most extensive population of distinctive ”Big Head” abalone shell pendants, which are believed to represent affiliation in the formally structured Kúksú religion. As a result, the Muwekma Language Committee decided to reclaim, by renaming this significant ancestral cemetery site “Mánni Muwékma Kúksú Hóowok Yatiš Túnnešte-tka” (Place Where the People of the Kúksú (Bighead) Pendants are Buried Site.)

The Coyote Hills represents a unique geological feature fronting the San Francisco Bay. The four mortuary mounds located within the wetlands, symbolically represents the interface between land and water which are part Central California Indian moiety (meaning halves) system representing the Land (Deer) and Water (Bear) moieties, that had reciprocal ceremonial responsibilities to the opposite moiety, especially during funerals and annual mourning anniversary religious rites. These sacred spaces and places must have also figured in their creation narratives as well.

A River of Salmon and A Land That Speaks

This area was home to the ancestral Huchiun Muwekma Ohlone people. In 2013, the City of Emeryville redesigned the Temescal Creek Park and installed these storyboard panels inspired by tales from Muwekma Ohlone heritage. The creek which was once a bountiful stream filled with salmon is now contained in a channel buried beneath the pavement.

Artist Erica Fielder contacted the Muwekma Tribal Leadership for help with the rendering, review, and translations of Ohlone words, stating:

“My interpretive displays are meant to show visitors to the park a tiny slice of what was once there. The City gave me the direction to create a panel on salmon and one on the Muwekma people. … The purpose of these displays is to convey a bit of the relationship people had with the land. Families, children, and neighbors to the park, will be seeing the panels.”

A River of Salmon and A Land That Speaks

Storyboard interpretive signs

Temescal Park, Emeryville

Artist: Erica Fielder

Photograph by Kike Arnal

Thámien Rúmmeytak (Place of the Guadalupe River Site)

Thámien Rúmmeytak (Place of the Guadalupe River Site)

Urban Development on ancestral Muwekma land; high-rise construction at 200 and 180 Park Avenue, San Jose

Photograph by Kike Arnal

Under the newly-constructed office building at 200 Park Avenue is the location of a major Muwekma Ohlone ancestral heritage cemetery and village site – formerly known as the Holiday Inn Site. The Chochenyo name of this site comes from the aboriginal name for this area of tribal lands, called Thámien by the Spanish priests who established the Mission Santa Clara in 1777. Tribal Leadership therefore decided to use the name Thámien as a name for the Guadalupe River, renaming it Thámien Rúmmey.

This ancestral heritage site, CA-SCL-128, is identified in archaeological reports as the Thámien Rúmmeytak, which translates to Place of the Guadalupe River Site. The 1977 construction of the Holiday Inn Hotel severely and adversely impacted this significant ancestral cemetery and village now buried under the new development.

By working collectively to obtain control of archaeological excavations of ancestral heritage sites, which serve as claims to their own history, the Tribe rejected the false narrative of their extinction. Through excavation work, they have documented their historical and cultural identity. By writing interpretive reports for sites such as this, the Muwekma Ohlone challenged the erasure of their culture and identity. What happened at the CA-SCL-128 site was the catalyst that initiated their collaborations with cultural resource management (CRM) firms, and the eventual establishment of the Tribe’s own CRM firm, which was led by former Tribal Chairwoman Rosemary Cambra.

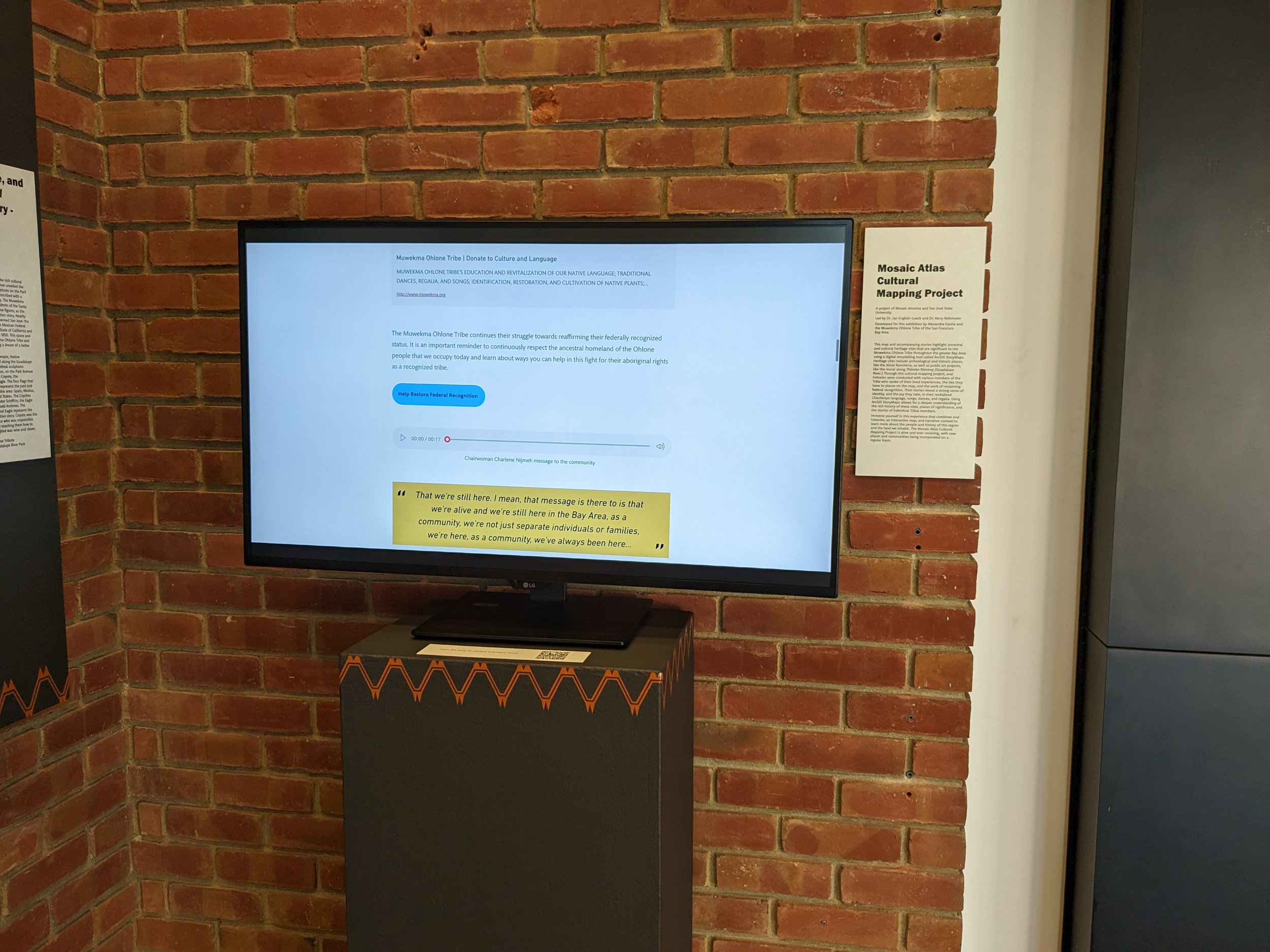

Mosaic Atlas Cultural Mapping Project

A project of Mosaic America and San José State University. Led by Dr. Jan English-Lueck and Dr. Kerry Rohrmeier. Developed for this exhibition by Alexandra Garcia and the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe of the San Francisco Bay Area

This map and accompanying stories highlight ancestral and cultural heritage sites that are significant to the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe throughout the greater Bay Area using a digital storytelling tool called ArcGIS StoryMaps. Heritage sites include archeological and historic places, like the Alisal Rancheria, as well as public art projects, like the mural along Thámien Rúmmey (Guadalupe River). Through this cultural mapping project, oral histories were conducted with various members of the Tribe who spoke of their lived experiences, the ties they have to places on the map, and the work of reclaiming federal recognition. Their stories reveal a strong sense of identity, and the joy they take, in their revitalized Chochenyo language, songs, dances, and regalia. Using ArcGIS StoryMaps allows for a deeper understanding of the rich history of these sites, places of significance, and the stories of individual Tribal members.

Immerse yourself in this experience that combines oral histories, an interactive map, and narrative context to learn more about the people and history of this region and the land we inhabit. The Mosaic Atlas Cultural Mapping Project is alive and ever-evolving, with new places and communities being incorporated on a regular basis.

Muwekma Ohlone Creation Story

Long ago it was said that Eagle, Coyote, and Hummingbird watched from the mountain tops the water recede after the great flood. Eagle, The Chief, sent Coyote to see if there was any land below. Coyote returned and announced that “the land is dry.”

Afterwards, Coyote made all the Indian people of California. He made the Muwekma (The People) of the Santa Clara Valley. Together, the Muwekma, Eagle, Coyote, Hummingbird and all the other animals shared this great and beautiful valley.

With the establishment of El Pueblo De San José De Guadalupe, the Coyote and the traditional Muwekma / Ohlone way of life became part of our valley’s rich historic past.

Muwekma Ohlone Flag

The official seal and flag of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe employs the image of a traditional Muwekma Dancer. It was originally sketched by Louis Choris, a naturalist and artist on the Russian scientific expedition ship, the Rurik (1815-1818). The colorized image was titled Tänzer der Californischen Indianer (California Indian Dancers) in an 1845 publication.

An examination of portraits sketched and painted by Louis Choris, whose images of Ohlone dancers at Mission San Francisco are well-known, suggests that both the dancer and the man on the left wearing feathered regalia are the same person; the unique structure of the headdress further confirms the provenance of these two colorized sketches.

The figure on the flag is dancing before the hills of the East and South Bay Diablo/Hamilton Mountain Range, and is surrounded by a traditional geometric basket design. On either side of the outer ring are two sprigs from a valley oak tree bearing acorns, one of the traditionally important foods for the Muwekma Ohlone people.

![(Place Where the People of the Kúksú [Bighead] Pendants are Buried) Coyote Hills](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54665323e4b07e4acef324f6/77390f9c-97a0-42bf-81a3-a98713172b00/__Coyote+Hills_6226.JPG)