Makkin Mak Muwekma Wolwoolum, 'Akkoy Mak-Warep, Manne Mak Hiswi!

We are Muwekma Ohlone, Welcome To Our Land, Where We Are Born!

Reclamation: Resilience of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe

Reclamation represents a continuation of NUMU’s ongoing partnership with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal of the San Francisco Bay Area, which extends back over 20 years. The present-day Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is comprised of all of the known surviving American Indian lineages aboriginal to the San Francisco Bay region who trace their ancestry through the Missions San Francisco, Santa Clara, and San Jose; and who were also members of the historic Federally Recognized Verona Band of Alameda County. The aboriginal homeland of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe includes the counties of San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, Contra Costa, and portions of Napa, Santa Cruz, Solano and San Joaquin.

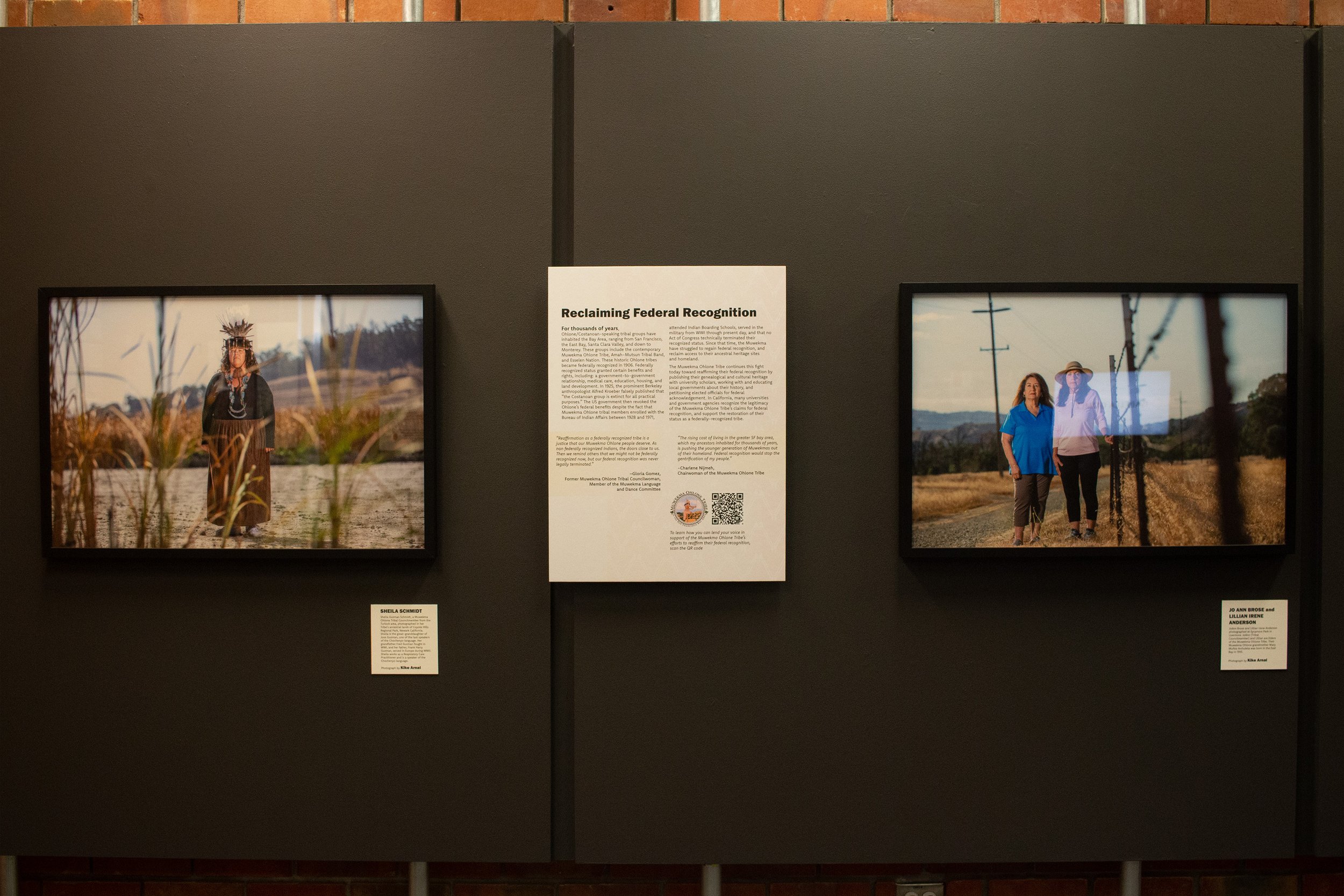

Internationally renowned documentary photographer Kike Arnal was designated Tribal Photographer in 2021, who has since documented Muwekma Tribal ceremonies, events, and daily life. In collaboration with the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe and San Jose State University Department of Anthropology, Reclamation: Resilience of the Ohlone Muwekma Tribe aims to promote deeper understanding of local indigenous art, culture, history, and contemporary issues in Los Gatos and the greater Bay Area, with a special focus on the critical issues surrounding federal recognition that the Muwekma Ohlone continue to fight for. Throughout the exhibit, look for links to learn more about the Muwekma, and ways you can support their efforts.

Reaffirming Federal Recognition

“Reaffirmation as a federally recognized tribe is a justice that our Muwekma Ohlone people deserve. As non federally recognized Indians, the doors close to us. Then we remind others that we might not be federally recognized now, but our federal recognition was never legally terminated.”

For thousands of years, Ohlone/Costanoan-speaking tribal groups have inhabited the Bay Area, ranging from the areas of San Francisco to the north, the East Bay, Santa Clara Valley, down to Monterey County. These groups include the contemporary Muwekma Ohlone Tribe, the Amah-Mutsun Tribal Band (Mission San Juan Bautista), and the Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen Nation (Mission San Carlos/Carmel).

Following multiple waves of invasion and colonization, beginning in 1769, these historic Ohlone tribal bands became federally recognized in 1906 as a result of the discovery of the 18 unratified treaties of 1851-1852. Federally recognized status confers certain benefits and rights, such as a government to government relationship, sovereignty, and funds available for housing, medical care, education, and land development. Then, in 1925, prominent anthropologist Alfred L. Kroeber falsely published and declared that “the Costanoan group is extinct for all practical purposes are concerned.” Despite the fact that Muwekma Ohlone tribal members enrolled with the Bureau of Indian Affairs between 1928 through 1971, attended Indian Boarding Schools in the 1930s-1940s, served in the military from WWI through present-day, and that no act of Congress terminated their recognition status, because of this declaration the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe lost all of their rights and benefits given to federally recognized tribes. Since that time, the Ohlone have struggled to regain federal recognition, and reclaim access to their ancestral heritage sites and homeland.

The present Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council continues this fight toward reaffirming federal recognition by researching their geological heritage along with university scholars, working with and educating local governments about their history, and petitioning the federal government for federal acknowledgement. In California, the County of Santa Clara, City of San José, San Francisco Board of Supervisors, and the California Secretary of State recognize the legitimacy of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe’s claims for federal recognition, and call for the US government to restore their status as a federally-recognized tribe.

“Federal recognition means the right of self-determination as a sovereign people. The right to build a Native Village for our tribal citizens where they can reside in their ancestral homeland and learn their language, their dances, their traditional and cultural ways without shame or fear of being marginalized, assimilated or erased.

The rising cost of living in the greater SF bay area, which my ancestors inhabited for thousands of years, is pushing the younger generation of Muwekmas out of their homeland. Federal recognition would stop the gentrification of my people.”

Reversing the Politics of Erasure

“[Politics of erasure means] basically, how we have been excluded or marginalized politically as Muwekma Ohlone people. How sometimes our government’s own laws can be used against us with loopholes and animosity to keep us from being acknowledged, appreciated, and respected.”

The Ohlone people of the San Francisco Bay Area have been denied their cultural existence, language, tradition, identity, and even their place names. Hispanic and Anglo-American colonial practices, such as missions, caused displacement, environmental degradation, and urban development and expansion that erased and replaced the presence of the social and cultural landscapes of the Ohlone tribes.

Mexican, Spanish, and United States colonial systems transformed the landscapes and maps of the Bay Area. The aboriginal homeland of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe includes the following present-day counties: San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, Contra Costa, and portions of Napa, Santa Cruz, Solano, and San Joaquin. The Spanish colonial expansion, particularly the mission system that resettled and scattered the native populations into corporate communities, paved the way for the U.S. annexation to disenfranchise and erase the Ohlone people. Native identity often was obscured, not just by being issued Spanish names, but by the terms used by Spanish officials and missionaries to classify people and establish their social place within the colonial society.

From 1839-1916, almost all of the Bay Area Indians found refuge at the Alisal Rancheria near Pleasanton and at neighboring rancherias at Niles, Sunol, Livermore, and San Leandro where they were able to safely practice the dances, traditions and speak their languages. Between 1906 and 1927 the Verona Band fell under the direct jurisdiction of the BIA awaiting the purchase of land for their homesites through the Congressional Appropriation Acts for landless California Indians.

The more recent acceleration in urbanization has led to sudden and significant demographic changes within the S.F Bay Area, thus further marginalizing and making invisible the Tribe. Ongoing colonialism is the driving force behind the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe’s unrecognized status. For the past two centuries, political, economic, and academic forces have continuously attempted to erase the existence of the Ohlone people of the San Francisco Bay Area.

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe is working to reverse the politics of erasure through several processes including:

Genealogical research and documentation of the enrolled lineages;

Conducting their collaborative archaeological work on their ancestral village and cemetery sites;

Co-authoring various archaeological, ethnohistorical, and scientific articles and publications;

Revitalizing their language, dances and cultural traditions;

Presenting lectures about the history and heritage of the tribe at various Bay Area universities, community colleges, high-to -elementary schools, and public events since the 1980s;

Submitting a fully documented petition to the BIA for their reaffirmation, working with elected officials to introduce legislation restoring the Tribe’s acknowledged status.

Ancestors + Identity

“My whole life, I’ve said I’ve been Native American, but when you attach that to also being unrecognized Native American, I’ve been asked: “Are you really Native American? Because you’re not recognized?” And I’m just like, well, of course I’m Native American. My blood says I’m Native American, my ancestors say I’m Native American. It’s affected me growing up because people have questioned my tradition, and me actually being Native American, because the government doesn’t recognize me.”

“I think what Noel feels is what we all feel. That we Muwekmas are considered less Indian than other Native Americans from federally recognized tribes. Almost as if we aren’t legitimate enough to be recognized.

But Muwekma’s existence and identity do not depend on federal recognition or acknowledgment of that recognition. The community, meaning the Muwekma People, make up the Tribe and we were a Tribal community long before the Federal Government recognized us.”

The current 600 members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe have a deep appreciation and value for their ancestors, and an immense feeling of responsibility to honor them through the cultural revitalization of their traditions today. The Muwekma Ohlone have extensive genealogical records of the Mission Baptism, Death and Marriage Records from the three Bay Area Missions tracing their lineages back to their aboriginal villages of the late 18th century right up to today.

The Muwekma Ohlone’s ancestors were able to survive as a tribe despite having no titled land of their own, and by seeking out a living by working on neighboring ranches, picking and harvesting crops, working as domestics and vaqueros, and later working for Southern Pacific Railroad and Leslie Salt for example.

Today, the post 1960s generation have been playing an important role in educating the current generation and teaching them the ways of the past in order to continue their traditions. Honoring the lives of their ancestors and the role they played in the preservation of culture, gives agency to current and future generations of Muwekma youth to tell their own story and find their place.

Tribal members today express how grateful they are to be related to their ancestors who are the reason why the Tribe has been able to maintain its identity, integrity, social fabric, and ultimately continue the fight for their rights today. Honoring the legacy and lives of ancestors is integral to the Tribe’s contemporary identity. They feel a responsibility to their ancestors to honor their memory through cultural revitalization, through public art, and to protect their ancestral homelands and sacred ancestral burial grounds, by honoring the history of the land, water and air we all breathe. The Muwekma Ohlone are assured that their ancestors are still watching over them today, their living generations represent a bridge, a special relationship between their past, present, and future. Former Chairwoman Rosemary Cambra had consistently stated “that if it wasn’t for our ancestors, we would not have life today.”

Younger Tribal members have expressed how complicated it is to navigate their Native identity growing up in the face of other tribes and people expressing confusion over the Muwekma’s Federal Recognition status. Gaining Federal Recognition is a crucial part of honoring ancestors, legitimizing the tribe in the eyes of the dominant society, and thus paving the way for future generations of Muwekma Ohlone to feel empowered in their Native identity, and to have access to basic rights accorded other tribes, such as financial aid when applying to Universities and other programs. Not having Federal Recognition directly impacts how community members navigate their identity in today’s world, and presents obstacles to the public understanding the truth about their history and heritage. Understanding where you come from deeply informs your identity. Understanding the history of the Muwekma Ohlone is a first step in all of us respecting the ancestral homeland of the Ohlone people that we occupy today.

Revitalization + Resilience

“We are revitalizing our language, and bringing back our dances. And we work on projects like this [exhibition], to show that we are still here, and this is what we look like.”

Reclaiming historic practices like language, songs, dance, regalia, and plant cultivation has fueled the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe’s revitalization movement. The Tribe engages in public education, art, and historical projects that highlight and honor their cultural heritage and history, consistently reaffirming their connection to their aboriginal ancestral homeland of the Bay Area. These diverse projects can include a traditional dance exhibition at the Stanford Powwow, presenting a land acknowledgement at a San José Earthquakes game,, planting a native garden at Stanford University, opening public events with prayers and welcoming ceremonies, or a Muwekma flag-raising ceremony at Chabot College in Hayward, among many others.

Community initiatives, such as the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe Language Committee established in 2002, began the quest to restore the Tribe’s native Chochenyo language. Now, the Muwekma conduct translations for parks, schools, universities, and their ancestral heritage sites and places of significance to the Tribe, such as Máyyan Šáatošikma (Coyote Hills) in the East Bay and the 3rd Mission Santa Clara Indian Neophyte Cemetery in their aboriginal language. They incorporate their Muwekma Ohlone language into their land acknowledgments for the organizations they partner with, including words such as Horše túuxi (good day, hello) and Kiš horše ’ek-hinnan (thank you). In March of 2022, the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe gathered within their ethnohistoric tribal Thámien Ohlone dialect-speaking territory (present day San José) to perform a revived ceremonial dance for the first time in over 125 years. Some of the enrolled Muwekma Ohlone lineages are directly descended from the Alson/Santa Agueda Thámien Ohlone dialect-speaking tribe, who were some of the first converts into Mission Santa Clara.

The Muwekma Ohlone Tribe continuously practices these traditions decade after decade to demonstrate that they are still here–and have never left or abandoned their ancestral homeland. The process of revitalization and resilience is empowering to the members of the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe who are protecting their heritage and traditions for future generations. Support the Tribe’s reclamation of their ancestral heritage areas and their cultural resilience by attending a Muwekma Ohlone Tribal event.

“As Native people, revitalizing and reclaiming who we are is very empowering. There’s a lot of dedication that goes with learning…We breathed life back into our language. It was not dead. It was sleeping. That’s why we called it a sleeping language.”

Here's How You Can Help

More Information About the Muwekma Ohlone Tribe

This Native American Tribe Wants Federal Recognition. A New DNA Analysis Could Bolster Its Case.

- Jane Recker | Smithsonian Magazine