In the Artist’s Studio featuring Warren Chang and Voice of The Fields, curated by Helaine Glick, were presented at New Museum Los Gatos between January 31 - June 16, 2019.

This virtual tour feature dual exhibitions showcasing the work of Warren Chang,

presented in the Mike & Alyce Parsons Reception Area and the Spotlight Gallery.

The Artist’s Studio & Process

An artist’s workplace can seem mysterious, an inner sanctum where a self-motivated individual works hands on, and alone.

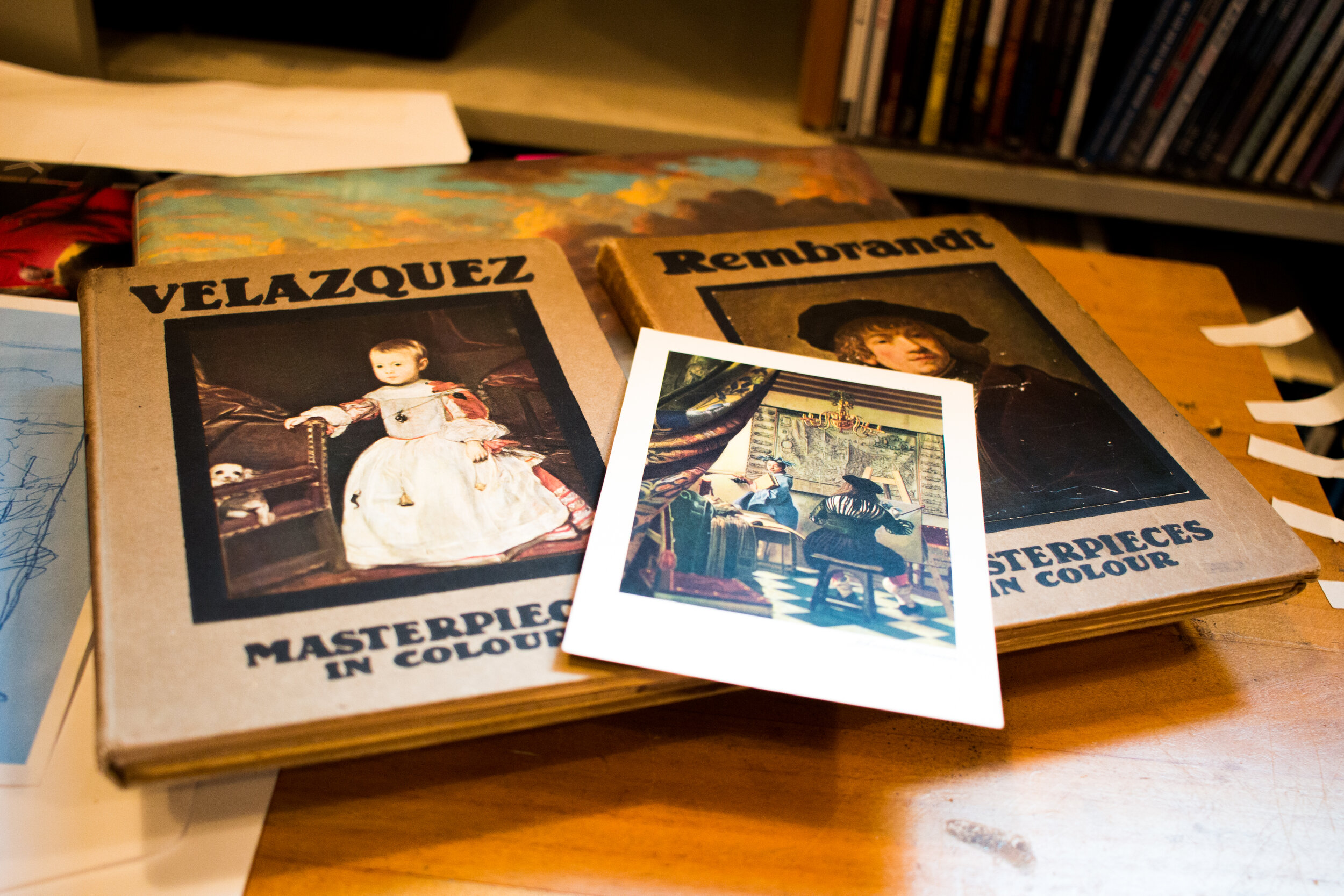

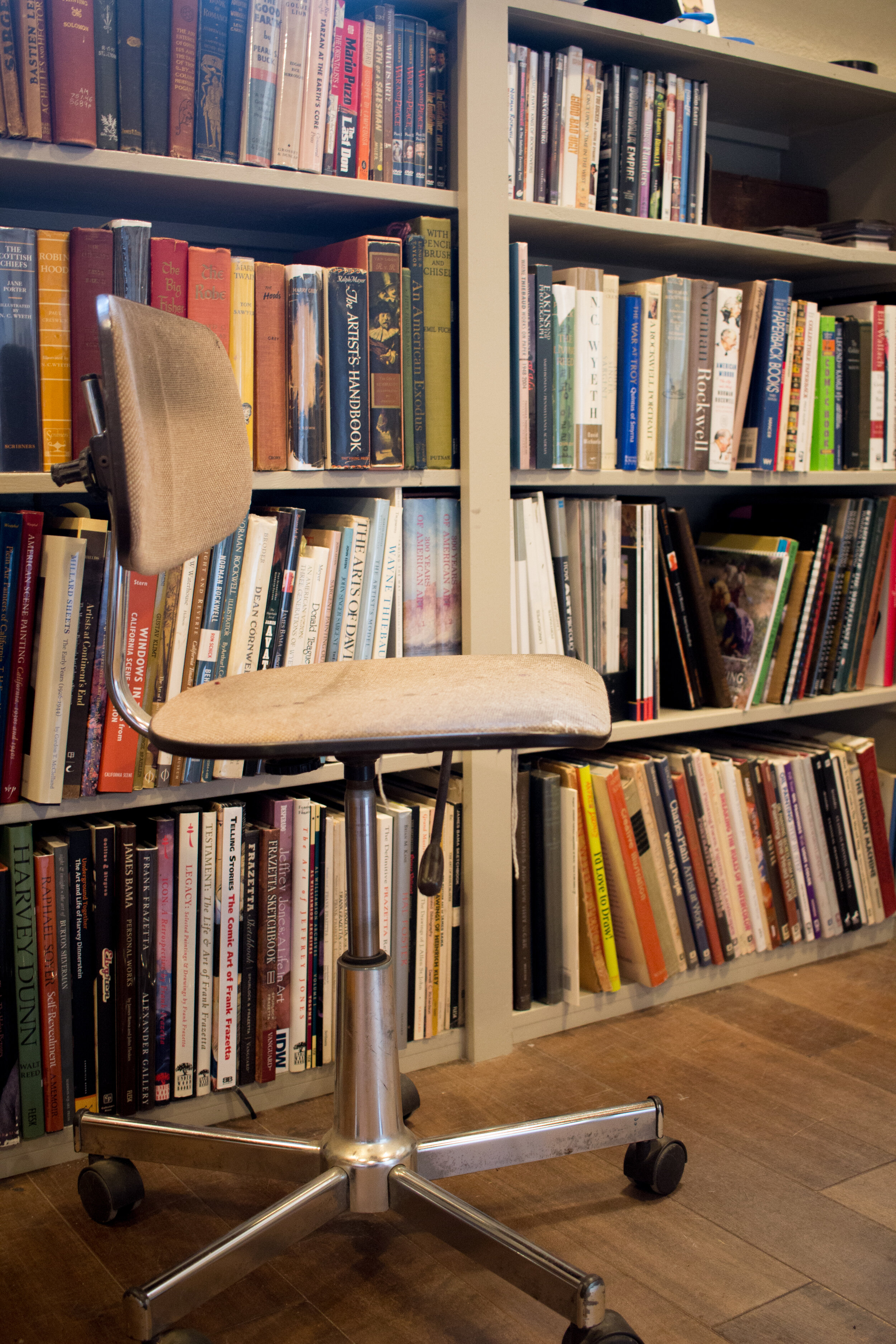

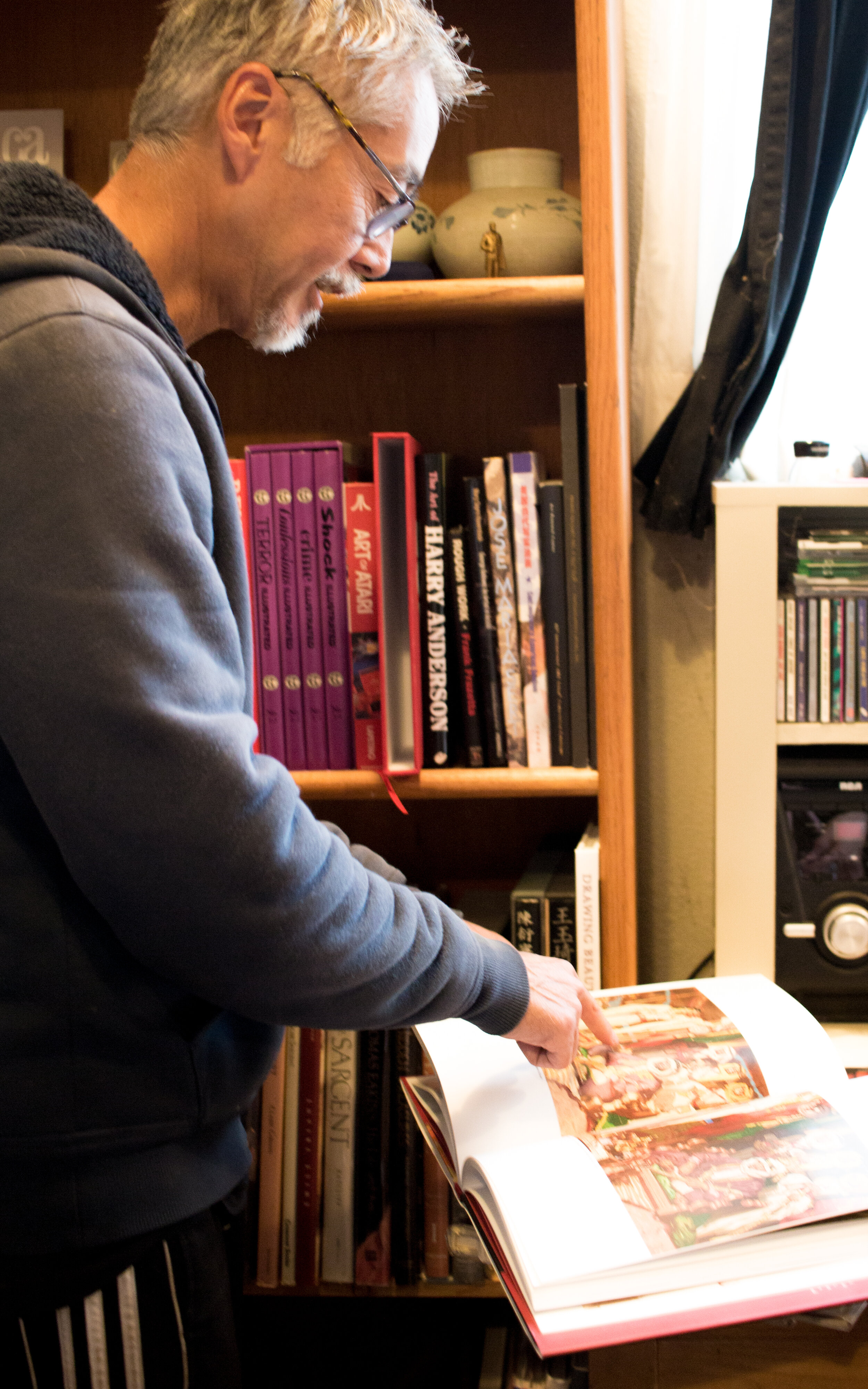

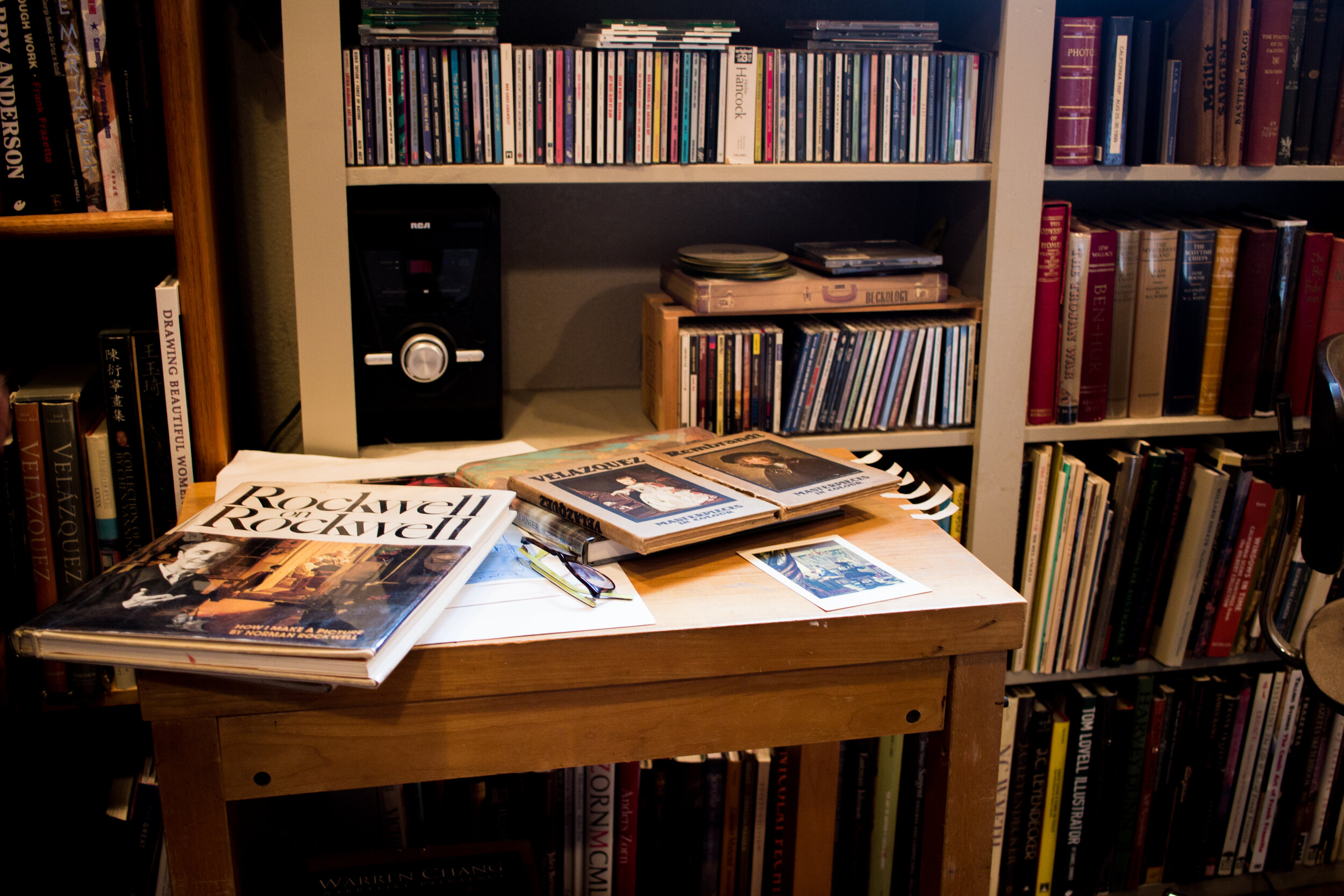

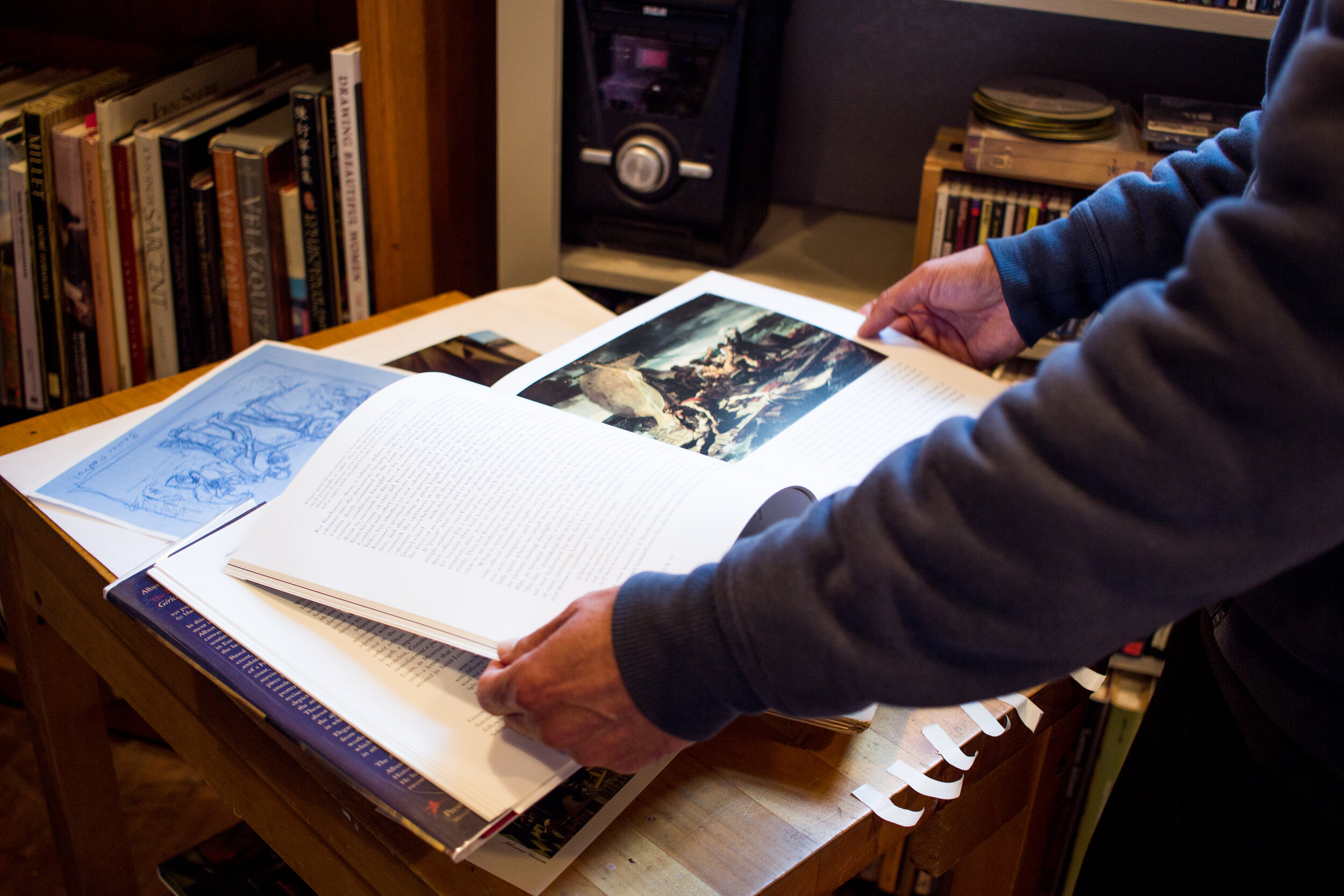

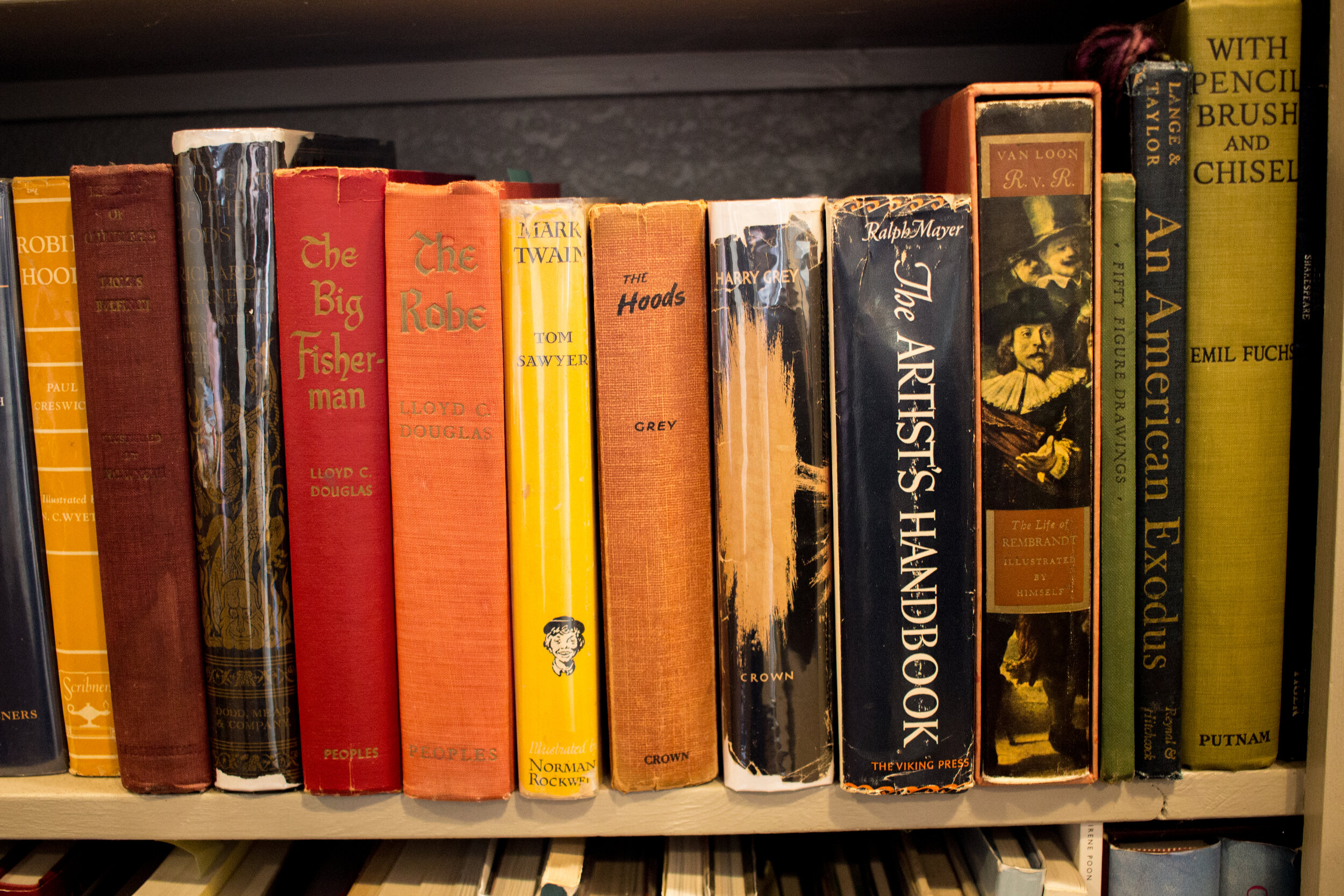

NUMU’s In the Artist’s Studio project provides a privileged glimpse into this intimate setting where the creative process takes place. Fine art painter Warren Chang’s cozy studio adjoins his home in the hills above Monterey’s Cannery Row. The space is stacked with canvases in various stages of development; an array of brushes, palette knives, tubes of paint and thinners rest conveniently nearby. Early works, a few sketches and a reproduction of a much-admired Velázquez masterpiece Las Meninas, hang on the walls. The bookshelves hold a variety of small models and objects, books on the philosophy, techniques and history of art, and catalogs of favored artists like Johannes Vermeer, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Jean-François Millet. An easel sits at one end in the best light, and a drop-down ladder leads to painting storage above.

In his own practice and as a long-time teacher of both illustration and fine art, Warren has spent countless hours in the studio environment, so the setting has made its way into his paintings. He recognizes the special flavor of these spaces and constructs multi-layered compositions in which he sets himself among students, family, or friends in a fascinating variation on self-portraiture. The culmination of these in-studio paintings, which he also refers to as “autobiographic interiors,” is the impressive Figurative Arrangement. Its imposing size, the muted tonality, multiple light sources, diverse group of figures, and especially the multiple paintings within (reproductions of his own works, including an earlier stage of this painting), clearly reference the classical structures and principles he has long studied. Figurative Arrangement is a remarkable achievement and an exceptional commentary on the pleasures and conundrums of representational art, and on the life of a visual artist.

About the Artist

Photo: John Fleskes

Warren Chang was born and raised in Monterey, California. He graduated from the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena in 1981, where he earned a B. F. A. with honors in Illustration. He went on to a successful twenty-year career as an illustrator in both New York and California, and taught at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, and the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. He continues to be an in-demand and popular teacher for museums, universities, and art guilds throughout California.

Almost twenty years ago Warren began studying fine art painting in New York with Max Ginsburg. He now belongs to the Oil Painters of America—the largest organization of its kind in the U.S.—and was one of only fifty artists to receive the honor of a Master Signature membership. His work has been featured in recent solo exhibitions at Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH and Monterey Museum of Art, Monterey, CA, as well as in numerous group shows throughout the United States. In addition, he has been both the subject and author of articles in numerous magazines, including International Artist, American Art Collector, Communication Arts Illustration Annual and Fine Art Connoisseur. His work has appeared in multiple exhibition catalogs including Exhibition of American Realism, Butler Institute of American Art, Painting California Seascapes and Beach Towns: Paintings of the California Art Club, Contemporary American Realism, Beijing World Art Museum, as well as his solo exhibition catalog Monterey Now: Warren Chang, Monterey Museum of Art.

Figurative Arrangement

Although Warren Chang’s paintings reflect his classical approach, they are more accurately a strategic blend of time-honored and contemporary processes. On the traditional side of the spectrum, he follows the practice of making a detailed drawing and a color study for each new work. These preparatory pieces act as maps for his final canvas, and sharpen his already refined abilities in composition and color. Continuing the process, he transfers the drawing to canvas and completes it with an underpainting in raw umber. This final step helps to solidify the composition and unify its tonal range. By the time he is ready to begin adding color, the necessary pigments are mixed and arranged on his palette.

On the contemporary end of the spectrum, a digital camera now takes its place with his sketchpad as an essential tool. Warren actively searches out subjects and locations for paintings as if scouting for a movie, and will impulsively pull off the road to snap a photograph or make a quick sketch of an interesting scene. In actual practice, fieldworkers may be unwilling or unable to pose for him, and may even balk at photographs. In these instances he will work from sketches and later enlist art students, friends and family to act as models for him. Like a director preparing actors for a part, he supplies them with clothing and props, and arranges them into position for a series of photographs.

Warren’s contemporary tools and techniques mesh seamlessly with the historic processes he has absorbed and emulates, and infuse his work with a depth and gravitas rare in art today.

Below is a glimpse into the step-by-step process shared by Warren Chang of his work on his 2014 painting, Figurative Arrangement.

One of my favorite subjects, and one that I have pursued for the past fifteen years has been, what I’ve called “Biographical Interiors,” or perhaps more accurately, “Autobiographical.” I am inspired by the works of the past, in particular many of the 17th century artists, such as Rembrandt, Vermeer and Diego Velasquez. My interior paintings depict scenes from my own life, such as self-portraits, scenes of family life, studio and classroom environments, as well as the people who inhabit them—myself, family, models, friends, other artists and art students. Since this subject is the life I lead, I’ve found it very personal to me and always evolving, as my own life changes and evolves.

This painting, which I completed over a five or six month span about five years ago, falls into this category of my work. I’ve titled it “Figurative Arrangement,” which is purposely an abstract title, rather than say, “Studio Visitors,” because to me, this is what the painting was about: an exercise in figure composition. It depicts a fictional gathering of friends and family to my studio, all in the efforts to lend me advice on my latest painting, which happens to be the very painting we are all depicted in. The painting was completed with the aid of photographic references. I mention this because many of my works are painted from life, without the use of photographic references. I believe it’s important to paint from life in order to exercise one’s skills and creativity and to better capture the spirit and essence of the subject. Having said this, I also believe that photography can be a very useful tool in creating art, even great art.

STAGE ONE: Thumbnail Sketch

The thumbnail sketch was drawn from my imagination with a ballpoint pen in my sketchbook (approximately 7 x 9”). This was used to help direct my subjects in their poses. It captures the gestures and movement of the figures and their arrangement. You can see my notes indicating who is posing where.

I believe this first idea sketch is the most important stage in the development of a painting. Many artists rely on random photographs to provide them with painting inspiration. Why not develop your own idea and make it happen! This is not to say that taking pictures first cannot result in good paintings, but why depend on chance or circumstance to determine your art? Sometimes an idea may lie in my mind for months, if not years, before I put it down on paper. It’s so rewarding to develop an idea, totally your own, and then put it in the work, to make it a reality.

STAGE TWO: Photoshoot

Despite my statement that the thumbnail sketch is the most important step, I actually believe that all these steps are important. Certainly, if you’re working from a photographic reference, the success of your painting relies on the success of your photo shoot. Ideally it would be great to have all the models, or “actors” as I like to refer to them, posing together, so they can be arranged in groupings of three or four. This way, issues of composition, overlapping figures and lighting can be handled all at once, solving any problems at the outset. Unfortunately this is not always possible, and in most cases I had to pose and photograph each model one at a time over a period of a week or even a month, according to everyone’s schedules. It’s more difficult to work this way, but if you are inspired, you just have to hold on to your vision, the thumbnail sketch being your foundation and key.

STAGE THREE: Final Drawing

I used black and white pencil on gray matte board to develop the final drawing, which measures about 20 x 30 inches. The main objective was to arrange and place the figures within the interior studio space. The drawing is line oriented in order to clearly define where each figure is placed, and uses just an outline to indicate certain objects.

Later I transferred this drawing to the final canvas using an opaque projector to roughly indicate where the figures and objects would fall. I also photocopied the drawing to a smaller size, to aid in projecting it larger, and to work on for the color sketch.

STAGE FOUR: Color Study

The final drawing was photocopied to a smaller size and pasted onto illustration board. I applied a layer of matte medium over the mounted drawing, so the oil paints would adhere to the surface. This color study was completed in a few hours, and pretty much serves to tell me how the final painting will look. Emphasis is on broad shapes and color, not on details.

Often, viewers have told me that the color study is more interesting than the final painting, and that they like it better! I can see their point. The color study is looser and captures all the feel of the final version without the “fuss.” For me, the joy experienced when making the color study comes from discovering the magic of how color and mood are achieved. It can leave the process of executing the final piece more of a mechanical exercise. Even though this may be true, I still think it’s the most effective way to achieve the best results when working on a larger scale.

STAGE FIVE: Underpainting

The underpainting was completed in raw umber, using turpenoid as a medium and thinner only. First, transferring the final drawing to canvas, I outlined it loosely on the canvas with vine charcoal, to rough in the placement of figures and my studio background. Vine charcoal is ideal for this purpose, as it rubs off easily and disappears as you apply oil paint. Then I proceed with a brush, using the vine charcoal outline as my guide as I refer to my photographic references.

This stage can take from one day to a couple of weeks, and because of its complexity this piece took me a couple of weeks to complete. This tonal stage resolves all the drawing, composition and values. The umber underpainting acts as a unifying agent for the color. Often I allow some of this umber underpainting to show through in the final painting, as it adds interest in the abstract painting surface.

STAGE SIX: Painting in Progress

I had this painting photographed at the halfway point to illustrate my process. You can see the passages of painted and unpainted areas of the underpainting. For this piece, I decided to concentrate on resolving the figures first and background environment last. In outdoor scenes I usually do the opposite; that is, painting the background first and figures and foreground last. I try to leave space in the areas surrounding the figures and heads so that when resuming I can paint more naturally back into passages without these areas looking too separate. It’s important for all elements to appear unified, particularly when painting multiple figures. How the head and figure relate to background in terms of edge helps to determine a sense of depth and atmosphere.

STAGE SEVEN: Finished Painting

The finished painting measures 40 x 60 inches. I decided to crop a few inches off the left, allowing the entrance of my father to bring the eye into the gathering and ultimately, to the focal point of the artist (me) seated in front of the easel. The shadows act as the unifying element of the painting. While color is revealed in areas of light, shadows remain a constant. They are relatively the same color and tonality, and help the figures read as a unit. Now, describing this process, I feel as if I’d relived it, and I’m sure you can understand how it can take five months to complete a painting of this size and complexity.

From left to right: My father Namgui Chang, my publisher John Fleskes, my wife Heather and older son Martin, my assistant Derek in the center, neighbors David and Royce McCornack, myself in the chair, and my younger son Matthew kneeling on the floor.

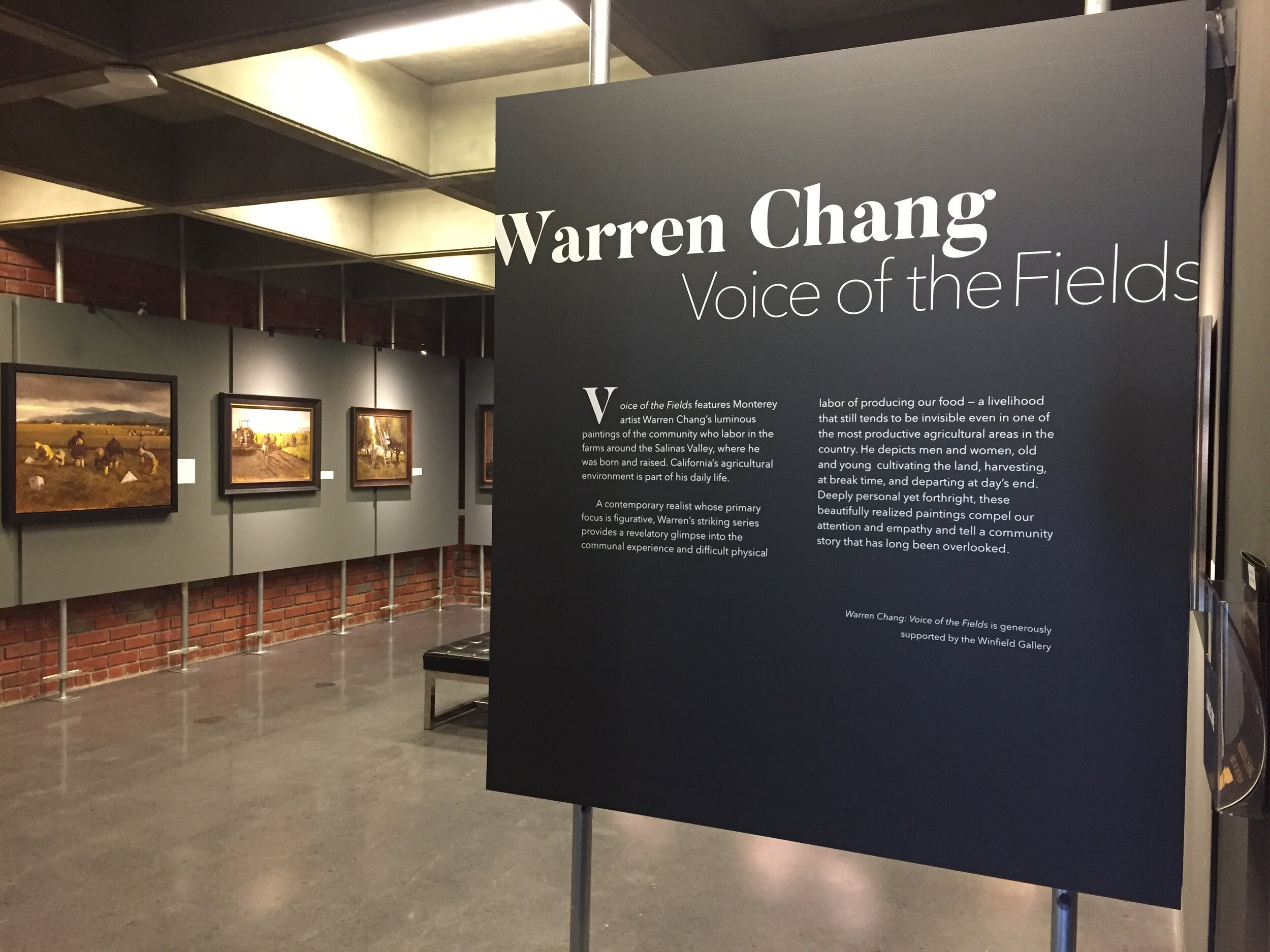

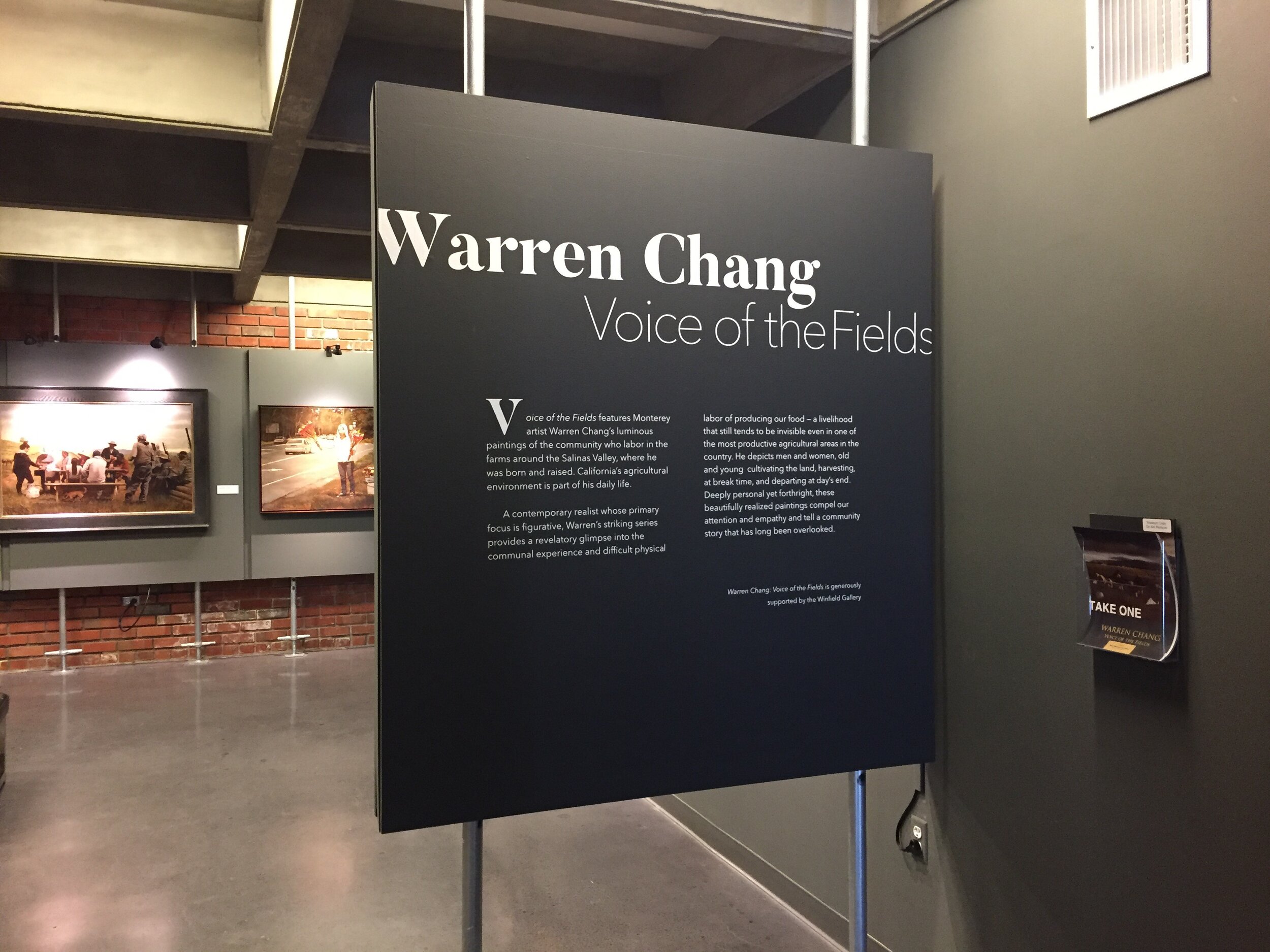

Warren Chang: Voice of the Fields

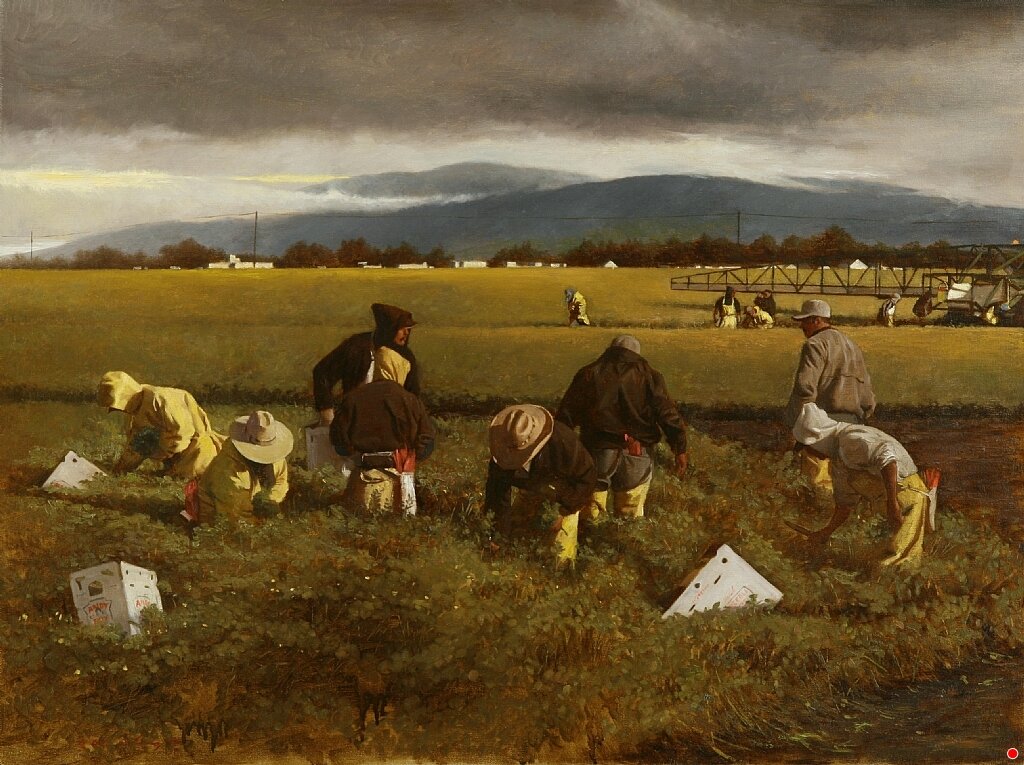

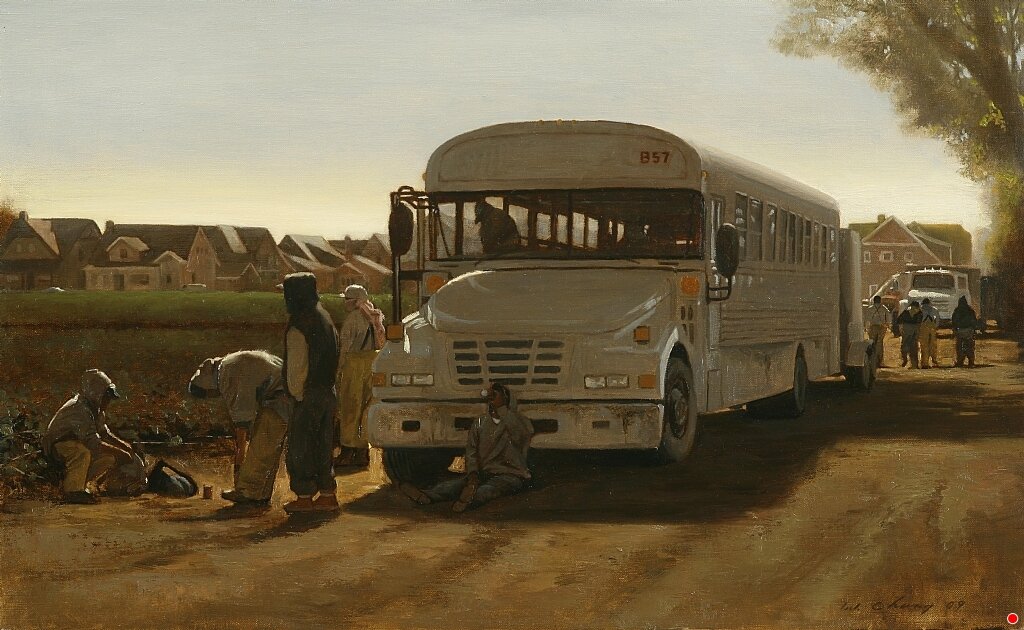

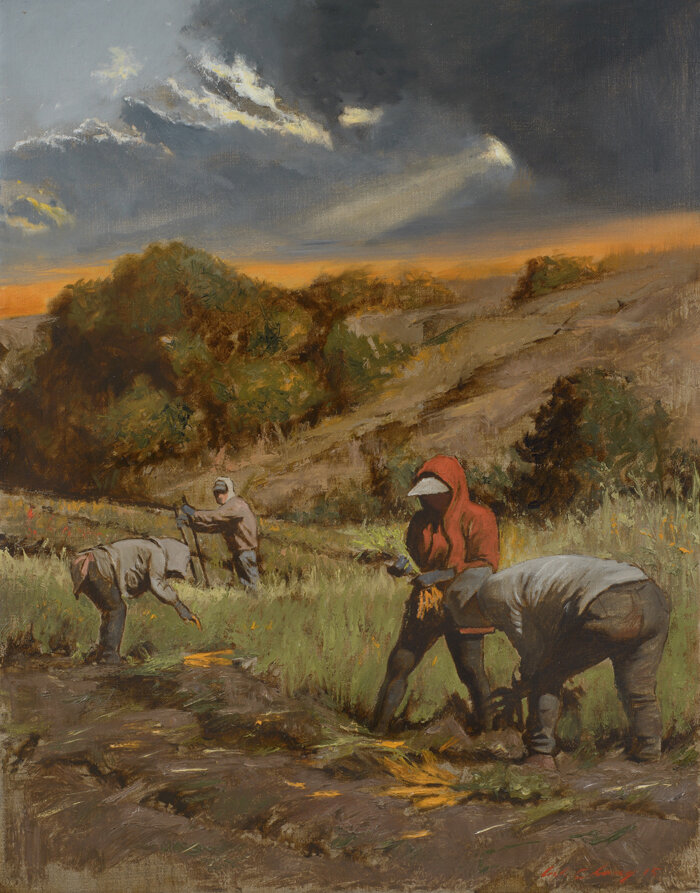

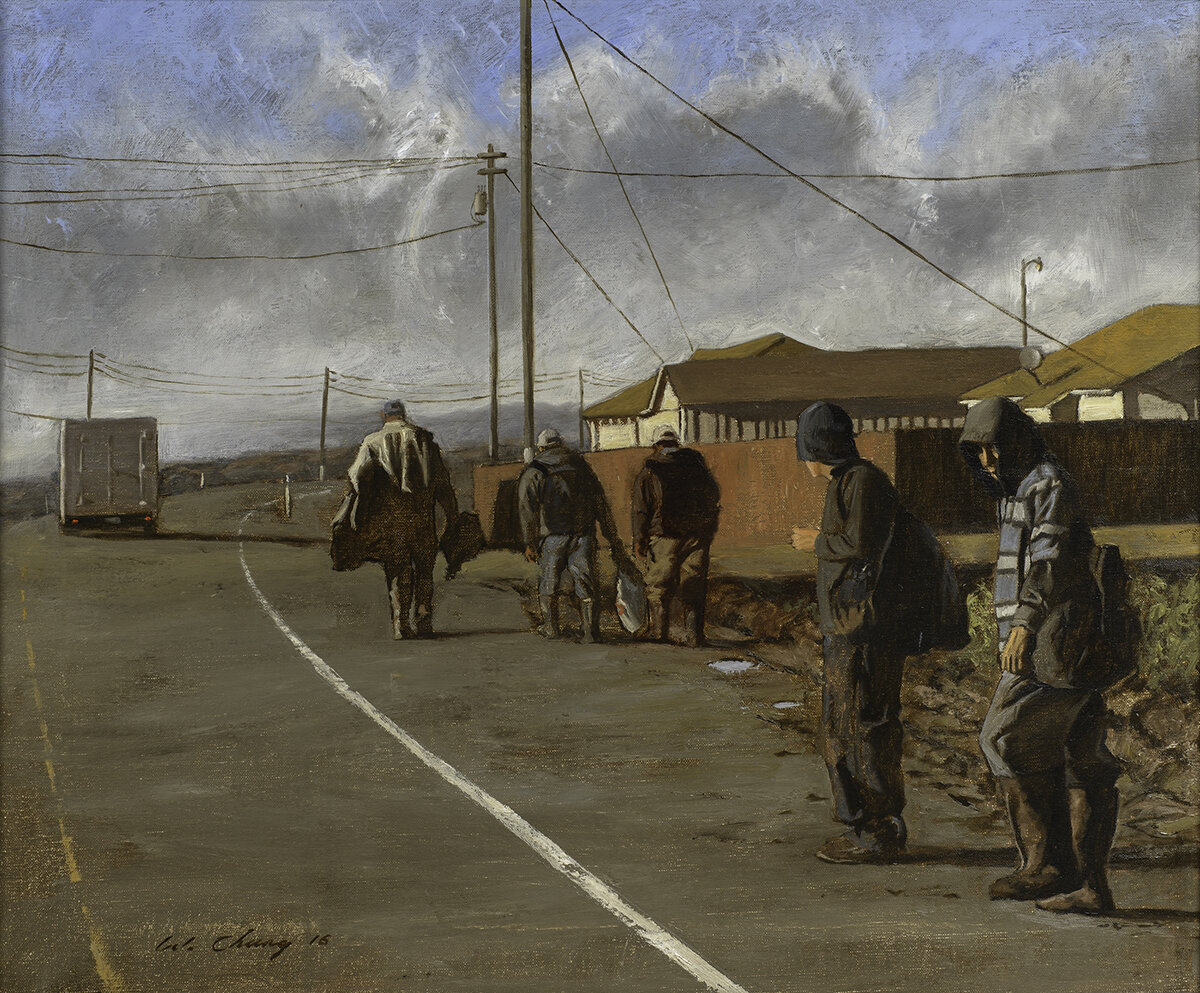

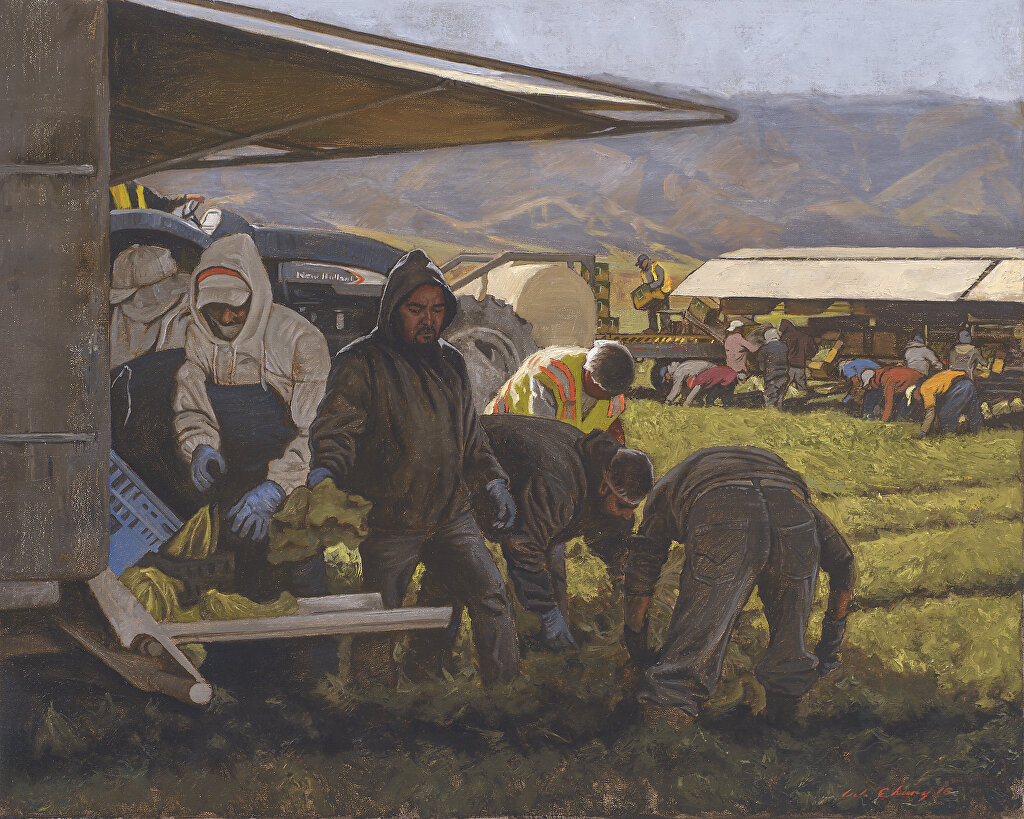

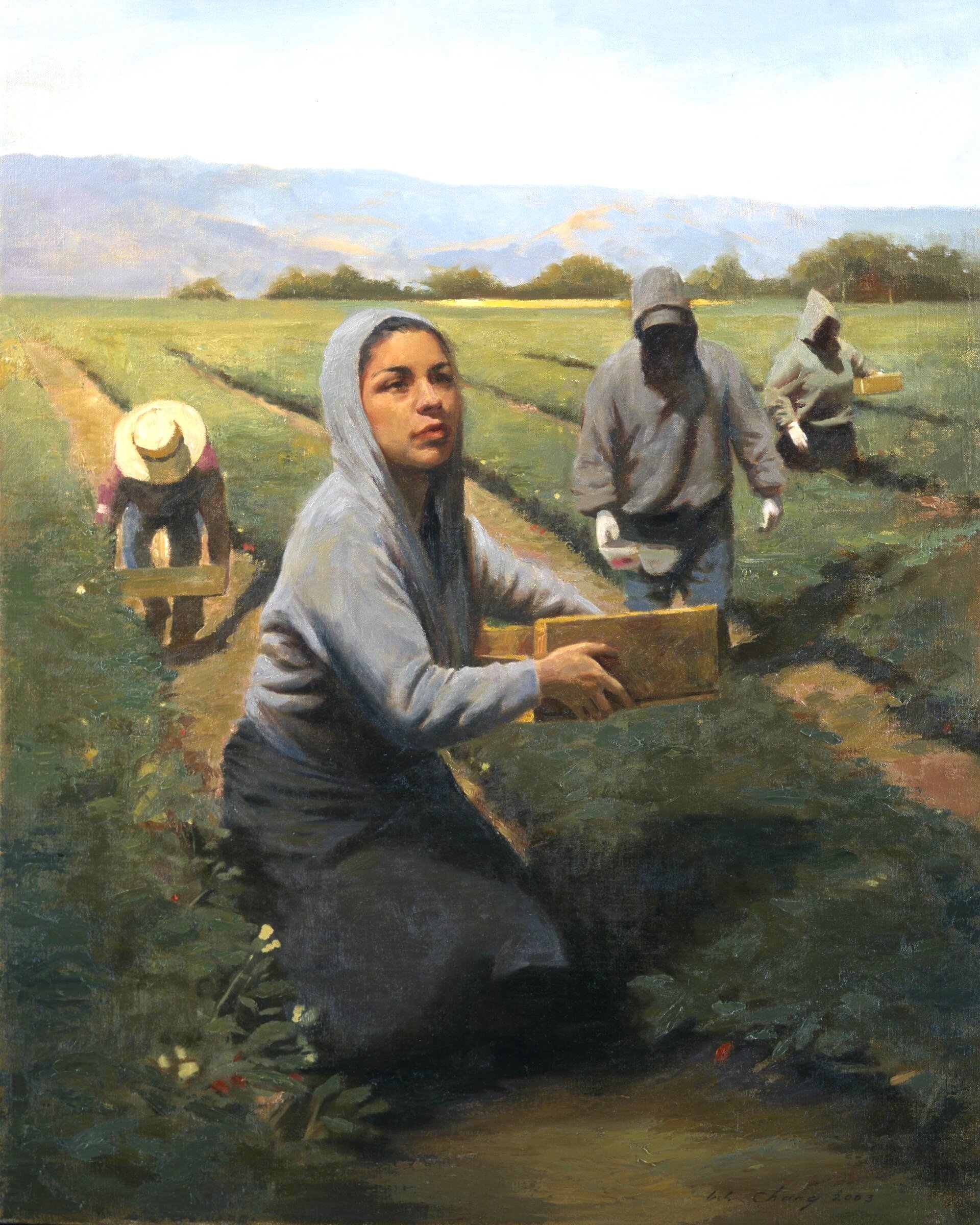

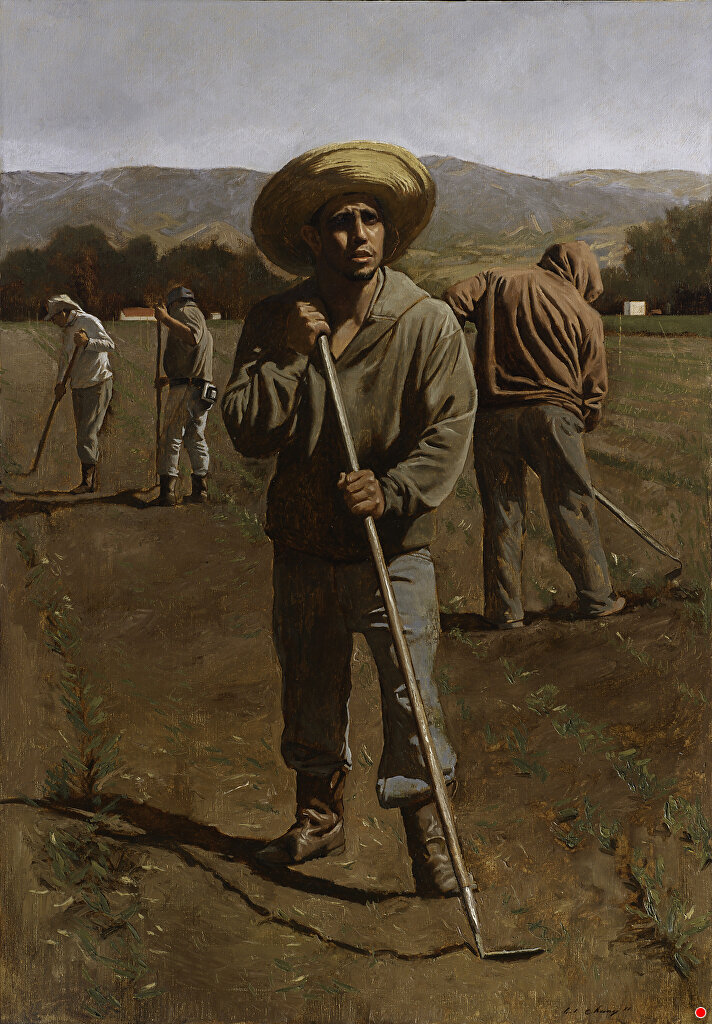

Voice of the Fields features Monterey artist Warren Chang’s luminous paintings of the community who labor in the farms around the Salinas Valley, where he was born and raised. California’s agricultural environment is part of his daily life.

A contemporary realist whose primary focus is figurative, Warren’s striking series provides a revelatory glimpse into the communal experience and difficult physical labor of producing our food — a livelihood that still tends to be invisible even in one of the most productive agricultural areas in the country. He depicts men and women, old and young, cultivating the land, harvesting, at break time, and departing at day’s end. Deeply personal yet forthright, these beautifully realized paintings compel our attention and empathy and tell a community story that has long been overlooked.

Influences & Inspiration

Warren Chang’s fieldworker paintings are rooted in everyday life. At heart he is a visual storyteller, describing in pictures the world he sees and experiences. His art is grounded in personal connection, and in the expression of deep philosophical and spiritual reservoirs. Multiple readings of Tolstoy’s What is Art? and the fiction of John Steinbeck led him to a worthy subject right in his own backyard—the fieldworkers of the Monterey Peninsula’s agricultural community, where he was born, lives and works.

Jean-FranÇois Millet. The Gleaners, 1857. Oil on canvas. 33 x 43 inches.

Warren finds much inspiration in the history of art, and studies the techniques and processes of the past. He especially favors the work of seventeenth century European masters Diego Velázquez, Rembrandt van Rijn, and Jan Vermeer, and like them he emphasizes figurative scenes from ordinary life. Yet, his fieldworker series more closely reflects France’s nineteenth century Barbizon School of realism, especially the work of Jean-François Millet. Millet’s 1857 masterpiece The Gleaners, was extremely controversial in its time. His naturalistic view of three peasant women laboring to gather a few leftover grains for food is the central focus of this large, exquisite work of art. It drew attention to the plight of the poor as he intended, but it also outraged many art patrons and critics because he appropriated the impressive format traditionally reserved for political, religious, or mythological heroes. The Gleaners is a milestone in the evolution of art and a precursor to modern painting.

Over one hundred fifty years later, Warren Chang’s fieldworker paintings are still unexpectedly relevant and eye opening. Like Millet, he reveals honestly and with elemental regard the experiences of people too commonly overlooked. His paintings illuminate the lives they depict so we can better appreciate and understand them. They demonstrate our shared humanity, and more accurately reflect the totality of life on the Monterey Peninsula.

NOTE FOR MOBILE USERS: Artwork title and descriptions can only be viewed on a desktop/laptop computer.

All images copyright of the individual artist. Do not use without permission.

In The Artist’s Studio featuring Warren Chang was made possible by the generous support of The Borgenicht Foundation. The Borgenicht Foundation supports social justice, conservation and historic preservation, the arts, health, and education.

Voice of the Field is generously supported by the Winfield Gallery.

All written content provided by the curator, Helaine Glick.