In 2016, NUMU partnered with the Muwekma Ohlone, the people indigenous to this area, to create an exhibition that highlighted the history, heritage, and legacy of their tribe. Today, as NUMU renews that partnership, we are sharing the content of that exhibition again throughout the month of November -- Native American Heritage Month -- in order to celebrate the Tribe’s vibrant culture, as well as acknowledge the continued existence of the Muwekma Ohlone peoples.

EARLY FEDERAL RECOGNITION OF THE OHLONE

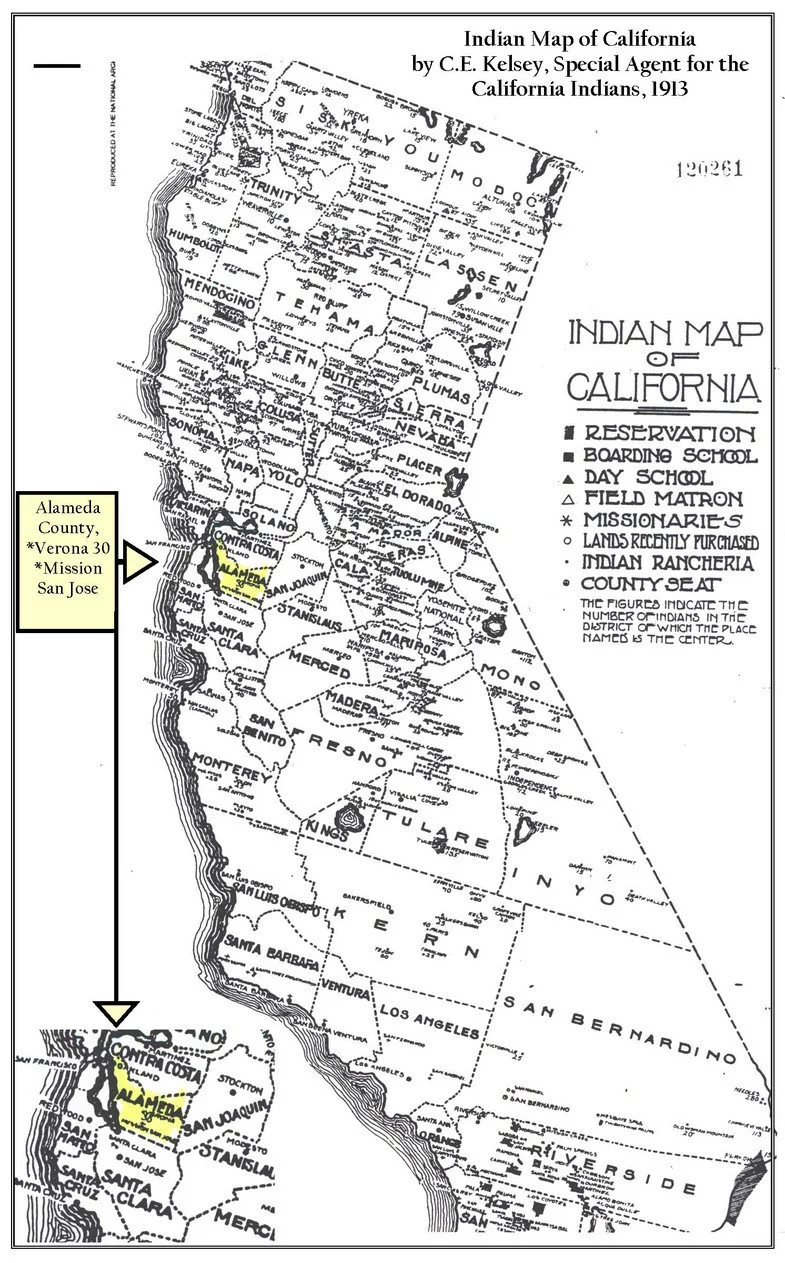

1913 map, which indicates that there were 30 Ohlones living near Pleasanton, and that they were federally recognized at the time.

In 1906, C.E. Kelsey, an attorney and activist from San Jose, conducted a special Indian census for the Bureau of Indian Affairs’ Branch of Acknowledgement Research (BAR). This critical survey proved that the Muwekma Ohlone, Amah-Mutsun, and Ohlone/Costanoan-Esselen had legitimate rights to the ownership of their ancestral lands, as indicated in the newly-discovered, unratified treaties of 1851.

REFUGEES IN THEIR OWN LAND

During the 19th and early 20th centuries, at least six Muwekma Ohlone communities emerged in the East Bay. These communities were located in San Leandro, Alisal near Pleasanton, Sunol, Del Mocho in Livermore, El Molino in Niles, and later a settlement in Newark. Many native arts, songs, and languages thrived at these locations for nearly 100 years. Eventually, they were forced to disperse because they had no legal claim to their lands as they were not fully recognized as citizens of the United States until 1924-1948.

Despite the dissolution of their communities, the Muwekma remained in the Bay Area and assimilated into the mainstream labor force. The Tribe maintained contact through their strong social ties, godparenting, and active culture. Members of the Muwekma Tribe maintained their legal status with the US government by registering with the BIA through the 1929 and 1971 enrollment periods.

ERASURE

In 1925, noted UC Berkeley anthropologist, Alfred L. Kroeber conducted a census of California Native Americans. Based on his limited definition of native culture at that time, Kroeber declared the Muwekma and other Ohlone tribal groups “culturally extinct.” His conclusions were influenced by the result of 200 years of Spanish colonialism, Catholic conversion, Spanish fluency, and mixed blood of California Native people.

Despite Kelsey’s census results, Kroeber’s claim of Muwekma extinction heavily influenced public, professional, and government opinion. The fallout was devastating. In 1927, the Superintendent of the Sacramento office of the BIA, L.A. Dorrington, inexplicably and illegally terminated 135 groups from the federal registration roll. These California tribes were then officially declared invisible in their homeland.

CALIFORNIA INDIAN CLAIMS ACT - 1964

In 1928, the Secretary of Interior approved the Muwekma Tribe’s pending California land claim. Over thirty years later, the decision to pay $325,000 to registered Ohlone tribal members for the “sale” of native land, specified in unratified treaties of 1851 and 1852, resulted in an allocation of $668.51 for each member. According to the government’s calculations, the land was valued at $1.25 per acre.

CHALLENGES

During the 20th century, the tribes continued to assimilate and live as a dispersed community. In addition to losing federal recognition and the benefits it awarded, the Muwekma Ohlone had to deal with the influx of indigenous people from out-of-state tribes to California due to the Relocation Program. Native Americans, of recognized tribes from elsewhere in the U.S., who relocated were eligible for federally-sponsored services, which the Muwekma Ohlone were continuously denied in their own homeland.

We acknowledge that New Museum Los Gatos sits on the ancestral land of the Ohlone, the Tamien Ohlone, and the Muwekma Ohlone people, who have stewarded this land throughout the generations. We recognize their connection to this region and give thanks for the opportunity to live, work, and learn on their traditional homeland. We pay respect to their Elders and to all Ohlone people, past, present, and future. This is one step towards creating a safe place for the community to learn from the past, dialogue about the present, and move forward.

To learn more about the Muwekma Ohlone Tribal Council and how you can support the Tribe, visit their webpage at muwekma.org and follow them on Facebook and Instagram.